Revolutionary Colours

In January 2011, a new term was added to the lexicon of politics and insurrection: Jasmine Revolution, referring to the popular uprising in Tunisia that toppled the regime of President Ben Ali. This is the most recent example of what have since 2005 been referred to as colour revolutions, which originally referred specifically to the changes of government in authoritarian former Soviet-bloc countries.

Colour revolution had been sparked by the unrest in Georgia in November 2003 that became known as the Rose Revolution and the similar uprising in Ukraine in 2004, the Orange Revolution. There have since been the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan and the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon, both in 2005, as well as the unsuccessful Green Revolution in Iran in 2009 that had been aimed at removing President Ahmadinejad.

As political scientists are fond of pointing out, colour revolution is a poor name. Only one of the group, Ukraine’s, strictly speaking refers to a colour (the Rose Revolution is from the flower). A better term might be floral revolution, though this is too delicate and frivolous for events of significance that are never without riot, bloodshed and destruction. However, few of them are revolutions in the strict literal sense of an armed insurrection, as they are principally mobilisations of civil unrest that unseat unpopular governments.

Some writers prefer the term soft revolution, which highlights the comparatively low-key nature of many of topplings of established authority. The classic example is the Czech Velvet Revolution of 1989, also sometimes called the Gentle Revolution, that non-violently overthrew the Communist government and led to Václav Havel becoming President.

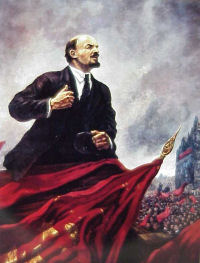

Lenin and the October Revolution

The granddaddy of all colour revolutions is the Red Revolution of 1917 that led to the creation of the USSR, though in that country it was always known as the October Revolution (the November Revolution in the rest of the world, since Russia was still on the old Julian calendar at the time). The colour, also in its symbol of the Red Flag, is a reference to the blood of the martyrs of the revolution that in the words of its anthem “dyed its ev’ry fold”. But the image of red revolution, without its initial capital letters — meaning any bloody revolt against the established order — is much older, having been applied to the French Revolution of 1848 and the Paris Commune insurrection of 1871.

Other uprisings of the twentieth century that provided models for the colour revolutions have included the Carnation Revolution of Portugal in 1974 (called that because some demonstrators wore carnations as badges of association) and the White Revolution, the name given to a package of reforms in Iran that was launched by the Shah in 1963.

A colour term in which revolution has been used in its figurative sense of a dramatic and wide-reaching change is Green Revolution for the developments in agricultural methods in the three decades after the end of the Second World War that greatly increased food production. William Gaud, the administrator of the US Agency for International Development, created it in a speech in 1968 in which he explicitly coined it by analogy with the Red and White Revolutions. Much more recently, the same figurative idea has been borrowed in India for its White and Pink revolutions, which respectively refer to the programmes to modernise and expand the country’s milk and meat industries.

Supporters of the Ukraine Orange Revolution

The names for the revolutions of the first decade of the twenty-first century have grown up from grass-roots level, sometimes stimulated by chance events, such as the Bulldozer Revolution in Serbia in 2000 in which a heavy vehicle, though not a bulldozer, was used to storm the TV station in Belgrade and helped to end Slobodan Milošević’s regime. Sometimes the image is an obvious one: Orange Revolution is derived from the campaign colour of the Ukraine leader Viktor Yushchenko, Rose Revolution from the flowers given out by supporters and especially the rose that the Georgian opposition leader Mikhail Saakashvili carried into parliament at one point, the Jasmine Revolution from the national flower of Tunisia. At times alternative titles have competed for domination: the Orange Revolution was also called the Chestnut Revolution, from the famous horse-chestnut trees that line the streets of Ukraine’s capital Kiev. Before Tulip Revolution was adopted the uprising was known variously as the Pink, Lemon, Silk and Daffodil revolutions (people carried daffodils as a symbol of support), before President Askar Akayev said in an ill-fated speech that there would be no Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan.

The online social media have become so important in linking and mobilising activists that the uprising in Tunisia has gained the alternative title of Twitter Revolution. The name was earlier given to the events in Moldova and Iran in 2009 and all three have also been described as Facebook revolutions, though the name hasn’t stuck in the same way. It’s too early to say which, if any of them, will be identified in the history books as the Twitter Revolution.