Newsletter 855

26 Oct 2013

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Brown as a berry A few readers creatively suggested that if grapes were called berries then dried grapes such as raisins would be brown enough to fit the description. Drying grapes to preserve them would seem to be as ancient as growing vines but drying them in our damp English climate would have been a chancy business. The evidence I’ve found is that in post-Conquest England raisins were imported as a luxury good. By 1300, they already had that name, so Chaucer would have been unlikely to call them berries.

Michael Keating wrote “The term may find its origin in the Anglo-Saxon for a bear. The colour brown was associated with bears in ancient French.” That’s an interesting suggestion, but bears were almost certainly extinct in Britain by the Anglo-Saxon period and brown as a bear isn’t on record.

Bo Bergman emailed from Sweden: “It might be of interest that the related Swedish word brun has or has had the meanings ‘black, dark; dark red; reddish-brown’. Swedish brunbär (literally ‘brown berry’) means ‘morello cherry’. In Old French brun could mean ‘a dark color between red and black, especially of the complexion’.”

“I have heard the term, brown as a berry, but infrequently,” wrote Terry Long. “My older relatives, many of whom were from the southern USA, would say brown as a nut. Parts of the southern USA used to have forests of nut trees, such as pecans and walnuts, so I would imagine such variation would come naturally.”

2. Help wanted

I’m looking for additional volunteer help to look over issues in draft. My British reviewer is finding it hard to comment regularly because of his commitments and I’m looking for somebody from the UK to supplement him. It involves carefully reading draft issues for sense and style and needs a person with editorial or journalistic experience. I usually email drafts the Sunday before the issue date and need comments back within 24 – 48 hours. If you’re interested, email me.

3. Manicule

Not to be confused with manacle or manicure, this is a much rarer word that also derives from Latin manus for a hand, in this case from the diminutive manicula, a little hand, which Romans also used for a plough-handle.

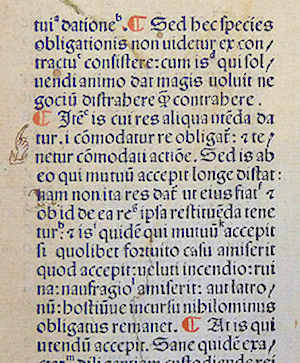

It has popped up through a discussion about it in a book on typography by Keith Houston, Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks (worth buying if you’re at all interested in the history of typography). A manicule is a hand with its first finger pointing, once used in the margins of manuscripts and books to draw the reader’s attention to passages of particular importance.

We often encounter it as a direction pointer in old-fashioned public signs, though these days we notice it most often as the vertical-pointing shape your computer’s cursor changes to when you pass it over a web link. Printers have given it a number of names, including fist and index. This last one is the official name, echoing the Latin word for a sign or pointer, as in index finger.

The history of manicule in English is a bit of a mystery. It isn’t recorded in the recent review of the letter M in the Oxford English Dictionary, nor is it in any other dictionary I’ve been able to consult. And I’ve found no example in print before 1996. However, William Sherman wrote in a detailed study of the sign in 2005 that he had been told it had become the standard term among scholars who study ancient manuscripts. I wonder if his informant actually had manicula in mind, either the Latin word or the identical Italian one; this has certainly been used in English-language works on manuscripts. Alteration of the final letter to turn it into an English equivalent seems to have happened very recently.

4. Snippets

Stag day The ninth annual World Bolving Competition was held last Sunday on the hills above Dulverton on Exmoor. Bolving is unique to Exmoor for what is known elsewhere as the belling or roaring of red deer stags at rutting time. Adrian Tierney-Jones described it in the Daily Telegraph in 2007 as “a mix of roaring lion, bellowing cow, chainsaw and someone severely constipated”. Stags produce a series of deep guttural sounds as a threat and challenge to other stags. The call has been imitated by hunters as a way to attract deer, although they have to be wary, as the unexpected arrival of several hundred kilograms of angry animal with big antlers intent on seeing off a rival is likely to ruin their day. The competition is just a fun event that was dreamed up in the local pub as a way to raise money for charity.

Seeing double The astronomical term circumbinary, which has been in the news recently, may not enthuse most readers. It becomes more engaging if the Star Wars planet Tatooine is mentioned, which orbits a double star and so is lit by two different suns. The concept has been dismissed by theorists as not being achievable even a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, because such systems would be too unstable to survive. But several such planets have been found in recent years, so that cosmology’s vocabulary has had to be enriched by two new words: circumbinary for the Tatooine type of planet and circumstellar for boring planets like Earth which only orbit the one sun.

5. Old besom

Q From Jane Tomlinson, Montreal: When I muttered old besom, when watching a local politician on the TV recently, was I unintentionally calling her a witch? Or was I merely taking a word beginning with b as a euphemism for female dog? Perhaps nobody else ever muttered old besom? It came up from the depths unexpectedly, I think a mild insult from my Lancashire childhood, a besom being a twig broom, very like a witch’s. I just wondered whether you might have any thoughts on the matter.

A I can assure you that old besom is a well-recorded insult that goes back many years, commonly with added expletives:

I’m a freeholder, with money in the bank; and now I won’t trust women no more! Silly old besom!

Rewards and Fairies, by Rudyard Kipling, 1910.

It isn’t yet obsolete but it’s definitely out of fashion, its fall in popularity partly due to the rarity of besoms in everyday urban life and perhaps also to the odd modern opprobrium attached to calling somebody old. It is still to be found in fiction:

It was unlikely that Rhea would have seen Susan’s face through the dense overgrowth of pig ivy even if the old besom had been looking in that direction, and she wasn’t.

Wizard and Glass, by Stephen King, 2003.

As you say, in standard English a besom is a broom made from twigs tied round a stick, a useful implement for sweeping up leaves and other loose stuff. If we are to go by the etymology of broom — always a most dangerous proceeding — anything called a broom really ought to be of the besom type, because its name derives from the use of the plant called broom to make besoms. Broom and besom have separated in sense in modern standard English, with only the latter now meaning implements made of twigs.

A seventeenth-century woodcut of a witch

A seventeenth-century woodcut of a witch

Besom as a term of mild contempt for a woman, especially one who is awkward or surly, began to appear in Scots near the end of the eighteenth century and is also known in several dialects of northern England, including Lancashire. It’s metonymy, a woman doing household chores by wielding a besom becoming known by its name. It may also be that an influence was the association of witches with broomsticks, always pictured as besoms. By the way, the Scottish National Dictionary says that in Scots broom refers only to the plant, while besom means any sort of sweeping instrument.

An early user was Sir Walter Scott:

“Ill’fa’ard, crazy, crack-brained gowk, that she is!” exclaimed the housekeeper, as she saw them depart, ‘to set up to be sae muckle better than ither folk, the ould besom, and to bring sae muckle distress on a douce quiet family!” If it hadna been that I am mair than half a gentlewoman by my station, I wad hae tried my ten nails in the wizen’d hide o’ her!”

Old Mortality, by Sir Walter Scott, 1816. Ill’fa’ard is “ill-favoured”; gowk is an awkward or foolish person, (though often as here a general term of abuse); a muckle (a variant of mickle) is a large amount; douce means sober or sedate.

One curiosity is that the two senses are pronounced differently. The broom is /biːzəm/  (bee-zum) while the disrespectful figurative version is more often /bɪzəm/ (biz-zum).

(bee-zum) while the disrespectful figurative version is more often /bɪzəm/ (biz-zum).

6. Sic!

• “Hyphen needed!” was the subject line of Greg Grove’s email about an online advert that appeared next to a crossword puzzle he was solving: “Join Dell, Microsoft and a guest expert for an in depth look at how OS migration can enhance security and end user productivity.”

• Gerhard Burger submitted a sentence from a Lifestyle column in the Johannesburg Sunday Times about a cycling event: “Roads, restaurants and bars were awash with tight Lycra-clad bottoms that spoke German or Spanish or surprised you with an English or Antipodean twang.”

• Such precision! A caption to a photograph of a Turkish coffee pot on the ABC website was spotted by Terry Karney: “Inexpensive models are listed for around $7 on Amazon, but more elaborate products with brass or copper can cost upwards of more.”

• Howard Sinberg sent in what he described as the non sequitur of the week, which he found in an article in the South Florida Sun-Sentinel about a ramen restaurant: “Despite opening in 2008, the restaurant still has customers who prefer to eat the soup but not the noodles.” He added, “And despite having been born in 1947, I am a retired electronics engineer.”

7. Useful information

World Wide Words is copyright © Michael Quinion 2013. All rights reserved. You may reproduce this newsletter in whole or part in free newsletters, newsgroups or mailing lists online provided that you include the copyright notice above. You need the prior permission of the author to reproduce any part of it on Web sites or in printed publications. You don’t need permission to link to it.

Comments on anything in this newsletter are more than welcome. To send them in, please visit the feedback page on our Web site.

If you have enjoyed this newsletter and would like to help defray its costs and those of the linked Web site, please visit our support page.