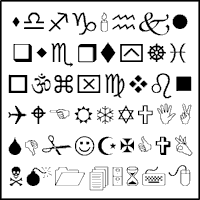

Dingbat

Q From Kelly Hogan: Thank you for the newsletter. I’d love to know the origin of dingbat, as in the ornamental characters used in typesetting.

Why are these called dingbats?

A It’s a rather splendid word, not least because it seems to have been considered useful for all seasons and situations. It is definitely American in origin and has been recorded as variously meaning a type of drink, a sum of money, a tramp or hobo, a bullet or cannonball (or generally any sort of missile), balls of dung on the buttocks of sheep or cattle. a foolish or insane person, student slang for a sort of muffin, an affectionate embrace, a term of admiration, or a vague and unspecified term for something or other whose real name the person speaking cannot bring to mind. The printing sense is a bit of a Johnny-come-lately within that jumble.

A note of warning should be uttered here. Several of these supposed meanings come from one source, a Mr Philip Hale of the Boston Journal in 1895. He had been collecting information on various senses, which was collated in an issue of Dialect Notes the same year. Several cannot be found in printed works. You may suspect Mr Hale of having been credulous or perhaps failing to check whether a speaker was using a real term or a temporary substitute for one he couldn’t for the moment recall.

Most examples in the nineteenth century were references to money:

“Rich widders are about yet,” said Nicky Nollekins to his friend Bunkers, “though they appear snapped up so fast.” ... “Well I’m not partic’lar, not I, (replied Billy.) nor never was. I’d take a widder for my part, if she’s got the ding-bats, and never ask no question, I’m not proud.”

Spirit of Jefferson (Charlestown, Virginia), 25 July 1848.

A later appearance not only illustrates another sense, but also gives us an indirect clue to the genesis of the term:

At the Methodist school at Wilbraham, Mass, the name “dingbat” has already been applied to a large raised biscuit that is brought to the table and eaten with butter or molasses in the morning. It’s palatable to the hungry, but is about as indigestible as a brickbat.

Placerville Mountain Democrat (California), 31 Aug 1878, in an item reprinted from the New York Graphic.

Brickbat? Could dingbat be a relative? It’s usually accepted that the ding part is from the verb to beat, knock or strike a heavy blow. A brickbat was an offensive weapon (though nowadays the assault is more often verbal) consisting rather obviously of a lump of brick. The bat in both cases was originally a stick or a stout piece of wood, the same word as in the modern baseball or cricket bat; it might be used for support or to defend oneself by battering an assailant. (Bat is from an Old French word meaning to beat.) The missile sense of dingbat is rarely recorded and that mostly during the Civil War, though there are references to its having been used in New England for something to chastise a child with.

Adopting dingbat for a thing whose proper name eludes one, a thingummy or doodad, appears late in the century:

He had gone to the symphony concert expecting to hear “After the Ball” with variations and “Daisy Bell” without them, but when they turned a whole raft of con motos and scherzos and op. 27’s and appoggiaturas and other chromatic dingbats loose on him he began to wonder what he was there for.

The Daily Independent (Helena, Montana), 31 Mar 1894.

Matron Brennan had occasion to use her sewing machine and found the shuttle and other dingbats belonging to the machine missing.

Dubuque Daily Herald, 21 Sep. 1898.

We may guess that printers took over the term as a convenient way of describing the miscellaneous set of non-alphabetic type symbols that are more formally called printer’s ornaments (though borders and flowery ornamentals are often separated out under the name of fleurons). Here Joe Toye, writer of a humorous column called What You May, overhears his text being proofread with the printer:

Head in a box. On the top line “the” in caps. Next line. What You May Column upper and lower. Third line in the box upper and lower. By Joe Toye with an “e” on the end of it. End of the box. ... Then come three dingbat stars and the next paragraph.

Boston Sunday Post, 24 Jun, 1917.

This is the earliest I’ve so far found, though I suspect that a bit of whimsy a decade earlier by C H Lincoln in his All Sorts column in another newspaper in the same city may derive from the same idea of a printing character (as indeed does his column’s title, as a sort is one character in a font of type):

Neither is the precious Dingbat the most hated of animals. We knew a printer who loved a trained Dingbat better even than he did his dog, and who spent many hours daily catching type-lice for it to eat.

Boston Post, 7 Jun. 1907. More on type lice here.

The sense of a stupid or crazy person starts to appear at about the same time, laying the foundation for Archie Bunker’s affectionate nickname for his wife Edith in the American TV show All In the Family.