Newsletter 904

25 Nov 2014

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Bridegroom. Following my piece on this word last time, several readers pointed out similar forms in other languages. Jim Muller noted, “The word for bridegroom is brudgom in Danish” and Klaus Floer mentioned that “This word is still alive in the German Bräutigam, which literally means ‘Man of the Bride’. This is the only instance where this word gam has survived.” Richard Mellish emailed, “It’s perhaps worth adding that the word is still brudgum in Swedish, though as in English the word gum by itself seems to have disappeared.”

Raymond Hopkins was puzzled by the Swedish word: “It is interesting that the word gumma refers to a woman, usually someone somewhat older, often the wife of the user of the word. Gubbe is the male equivalent. Such terms are in everyday use, at least in this part of Swedish-speaking Finland. If the words are related to the guma of the article, I can’t help wondering why the gender change.”

Peter de Vries found another linguistic oddity, “I’ve just remembered that in Dutch, the groom is called the bruidegom — so you appear to have very neatly explained the origin of gom for me! I’d often wondered about it, since gom also means gum — and as a kid I found it hard to conceive of a connection between marriage and chewing gum.”

2. Mammock

Ken Hopson emailed me a copy of a letter he had found in the Amherst County courthouse records of Virginia. A farmer sent it in March 1896 to the Southern Railway, claiming recompense for a bull that had been severely injured by a train:

i tell you he is no better than ded and i wish you wod make your secshun boss repote him as ded and pay me for him as an animile kild on the rale rode he is certanly unqualifided for a Bool and is too mommoked up fer a stere and he is too tuf for befe.

In the American South you may still hear mommocked up or mammocked up for mangled, mauled, torn to pieces or severely beaten. The word is conventionally spelled mammock in the new dictionaries that contain it and the verb by itself is said to mean not only tear to pieces, but also more loosely to botch, mess up, mix up or confuse. Mammock on its own has also referred to getting a severe beating:

All disciplined men of the fighting forces were knocked about until their skins became as red or blue as their jackets, and were sometimes even mammocked to death.

History of Penal Methods, by George Ives, 1914.

It has been widely known in English dialect. A century ago, the English Dialect Dictionary recorded it in a group of miscellaneous senses, for fragments of food, an untidy mess or muddle, a scarecrow, an absurdly dressed person or a poor eater. Its entry does have mammocked-up, but recorded it only from Shropshire for a person “dressed up fantastically and absurdly”. Noun and verb are recorded from the sixteenth century and Shakespeare used the verb in Coriolanus: “He did so set his teeth, and tear it. / Oh, I warrant how he mammockt it”.

The best that professional etymologists can come up with is that it might be from an imitation of the sound of chewing or muttering. They point to the obsolete British English mamble, to mutter, or eat without appetite. A relative was mumble, which began life with the idea of trying to eat with toothless gums, a condition that led to our modern sense of a person speaking indistinctly. Somehow mamble shifted to tearing at food with one’s teeth.

Something similar may have happened with mammock and from that meaning it diverged into its numerous other senses.

3. Mx

Mx was created on the model of the other personal titles Mr, Mrs and Ms for a person who doesn’t identify themselves as either male or female or doesn’t want their gender to be known.

An article in the Guardian on 17 November — prompted by the news that the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) was considering introducing it — noted the quiet rise in the use of Mx as a gender-neutral title, particularly in the UK. Mx is accepted as a valid title by a number of organisations, mostly in the public sector. The Post Office was first in 2009; it has since been joined by several governmental bodies, including the National Health Service, HM Revenue and Customs and the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. But other than those, acceptance is patchy and uncommon; the proposal by RBS marks a potential shift into the private sector, though RBS is 80% owned by the government.

Research by Nat Titman shows that Mx was created in online discussion groups in the early 1980s as a way to avoid identifying oneself as male or female or avoid specifying one’s marital status. It’s hard to say how often it was employed in real life in the following two decades but its sporadic appearances online argue for its being very rare. Around 2000 Mx began to be discussed by transgender and androgynous people, who have since led efforts to gain recognition for it.

This is the earliest example I can find in a British newspaper:

Official forms in Brighton and Hove will include the title “Mx” to cater for the city’s transgender community after a review of services. Brighton and Hove Council’s trans-equality scrutiny panel recommended removing the need for people to identify themselves as male or female at GP surgeries and introducing gender-neutral lavatories and changing rooms.

The Times, 4 May 2013.

It’s said as mix or mux, sometimes mixter.

4. Stepney

Q From David Vickery: Living and working in Saudi Arabia for 12 years brought me in contact with many different nationalities. One day I was out with one of my Indian colleagues when we had a puncture and he immediately asked if we had a Stepney. Having never heard of the term I finally deduced it to be the spare wheel. It’s a term not used in the UK. Any comments?

A This odd-sounding term for what we in Britain call a spare wheel or Americans a spare tire is known in some countries of the former British empire and colonies, including India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Malta.

The story begins in 1904. At this time, motor-cars weren’t supplied with spare wheels or tyres and motorists had to provide their own. Roads then were often very poor, punctures were frequent and few facilities existed for repairs away from base. Then as now, it was hard to replace a tyre on a wheel without specialised equipment and a spare had to be a wheel with tyre already fitted. That may sound like our common modern spare, but wheels then were often of wood or heavy metal construction and a spare was both bulky to carry and clumsy to replace.

Two entrepreneurs, Thomas Davies and his brother Walter, who ran an ironmongery business in Llanelli in south Wales, came to the rescue by inventing a clever device. It consisted of an inflated tyre on a circular metal rim without spokes. The motorist clamped it to the rim of the wheel that had the flat. In a share prospectus in December 1906, the brothers claimed “No levers or spanners are required to fix it. It is firmly secured by two simple butterfly thumb screws” and added that cars didn’t require jacking up to get the spare wheel on.

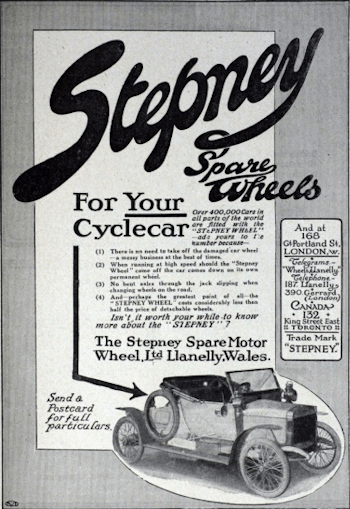

Above: A Stepney spare wheel and tyre (Image courtesy of Carmarthenshire Museums); Below: Advertisements from 1907 and 1913 (Images courtesy of Grace’s Guide)

They called their device the Stepney Spare Wheel, after the location of their workshop in Stepney Street, Llanelli. They patented the wheel and started to market it in January 1906, selling seven in the first month. By August that year, almost without advertising, they were selling 1,000 a month and realised they had a success. They formed a company, the Stepney Spare Motor Wheel Limited, and began to market the wheel in Britain, Europe and the British empire and colonies. They attempted the US in 1907, but like many British businesses that have tried to break into that market they quickly failed, in part because they were ripped off by local imitators.

Elsewhere, they enjoyed great success. In a court case in 1911, it was said that in Britain alone £250,000 worth had been sold (equivalent to about £25 million today) and that the wheels were seen on nearly every motor-car on the road. In 1912 the firm was claiming that 99% of all taxis in the world were fitted with Stepney spares. The business died out in Britain after the First World War because manufacturers began to provide proper spare wheels that were relatively easy to fit. However, in many countries, Stepney became synonymous with spare wheel and, as you’ve discovered, in some it remains common, though not in Britain nor, for the reasons I’ve given, the US.

For British people today, Stepney means only the east London suburb, which has led one researcher to falsely connect the device to the Stepney Ironmongery Company, which was situated there in the same period. It does seem odd that the name turns up in south Wales but there’s a good reason for it. Stepney had become a surname in London — like so many it had been borrowed from the place where the family originally lived. One member of the family went to south Wales in 1559; that branch became prosperous landowners and baronets (their Georgian house in Llanelli has recently been restored and reopened) and in the nineteenth century they developed the town as a port and industrial centre based on coal mining and tinplate manufacture. They provided the first mayor and paid for the coat of arms of the borough in 1912. One website claims that the fame of the spare wheel led to a picture of it being incorporated in the arms; not so, though it did appear on the borough’s badge and a blue and yellow chequered pattern on the coat of arms repeated part of the arms of the Stepney family.

They gave their name to Stepney Street and other locations in Llanelli and so indirectly to an almost forgotten episode in motoring history and an odd linguistic survival.

5. Sic!

• On 17 November, the Guardian reported on an auction of Napoleonana: “A white cotton shirt worn by the former emperor on St Helena, with a button missing estimated at between €30,000 and €40,000, went under the hammer at €70,000 (£56,000)” Expensive button.

• A report in the same paper two days later about Prince Charles noted a odd fashion choice: “Charles was burbling greetings in a husky baritone to a line of dignitaries who wore pinstripes and fascinators.”

• On 17 November the Daily Mail commented on British politics: “Douglas Carswell became the first elected Ukip MP last month when he won the Clacton by-election he called after defecating from the Tories.” The misleading intrusive a has since been removed.

• Al Segall found this on the aviation site airnation.net, dated 19 November: “Air Lair is a personal cocoon for the passenger with a double-decker configuration.”