Newsletter 928

01 Oct 2016

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Two pieces in this issue are rewrites of ones created more than a decade ago and which have been updated as a result of new information.

2. Tomfoolery

Q From Joe Brown: I was wondering where the phrase Tom Foolery came from?

A I would write it as one word, tomfoolery, and my ordered ranks of dictionaries tell me I’m right. But it often turns up in print in the way you have written it, or as Tom foolery or tom-foolery or Tom-foolery. Such forms show that their writers still link the word with some fool called Tom, even though they may not know who he was.

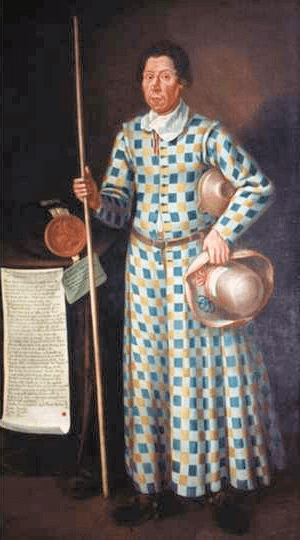

A portrait of Tom Skelton.

It is sometimes claimed that the original Tom Fool was Thomas Skelton. He was a jester, a fool, for the Pennington family at Muncaster Castle in Cumbria. This was probably about 1600 — he is said to be the model for the jester in Shakespeare’s King Lear of 1606. In legend, he was an unpleasant person. One story tells how he liked to sit under a tree by the road; whenever travellers he didn’t like asked the way to the ford over the River Esk, he would instead direct them to their deaths in the marshes. Another tale links him with the murder of a carpenter who was the lover of Sir William Pennington’s daughter.

So much for stories. In truth, Tom Fool is centuries older. He starts appearing in the historical record early in the 1300s in the Latinate form Thomas fatuus. The first part served even then as a generic term for any ordinary person, as it still does in phrases like Tom, Dick or Harry. The second word means stupid or foolish in Latin and has bequeathed us fatuous and infatuate, among other words. By 1356 Thomas fatuus had become Tom Fool.

Around the seventeenth century, the character of Tom Fool shifted somewhat from the epitome of a stupid or half-witted person to that of a fool or buffoon. He became a character who accompanied morris-dancers or formed part of the cast of various British mummers’ plays performed at Christmas, Easter or All Souls’ Day.

A tom-fool was more emphatically foolish than an unadorned fool. Tomfoolery was similarly worse than foolery, the state of acting foolishly, which had been in English since the sixteenth century. Perhaps oddly, it took until about 1800 for tomfoolery to appear. It had been preceded by the verb to tom-fool, to play the fool.

3. Fair to middling

Q From John Rupp, Dallas, Texas: I have often heard the phrase fair to Midland (middlin’?) in response to the inquiry ‘How are you doing?’ Any ideas on the origins of this phrase?

A As you hint, the phrase is more usually fair to middling, common enough — in Britain as well as North America — for something that’s moderate to merely average in quality, sometimes written the way people say it, as fair to middlin’.

With an initial capital letter, fair to Midland is a Texas version of the phrase, a joke on the name of the city of Midland in that state. A Texas rock band called themselves Fair to Midland after what they described as “an old Texan play on the term ‘fair to middling’”. American researcher Barry Popik has traced it to May 1935 in a report in the New York Times, “Dr. William Tweddell ... is what might be called a fair-to-Midland golfer.”

But we do occasionally see examples of fair to midland in American contexts without a capital letter and without any suggestion of humour:

While overall attendance was fair to midland — the championship session drew about 800 — the Bartlett student section was outstanding.

Daily Herald (Arlington Heights, Illinois), 31 Dec. 2011.

This lower-case fair to midland version is recorded in Massachusetts in 1968, which suggests that even then it had already lost its connection with Texas. It might be folk etymology, in which an unfamiliar word is changed to one that’s better known. But it’s an odd example, as middling isn’t so very uncommon. It may be that people tried to correct middlin’ to a more acceptable version that lacked the dropped letter but plumped for the wrong word.

All the early examples of fair to middling I can find in literary works are similarly American, from authors such as Mark Twain, Louisa May Alcott and Artemus Ward. To go by them, it looks as though it became common on the east coast of the US from the 1860s on. However, hunting in newspapers, I’ve found examples from a couple of decades before, likewise from the east coast. This one was in a newspaper review of the current issue of The Ladies’ Companion:

These three articles are the best in the present number — of the rest, most are from fair to middling.

Boston Morning Post, 6 Feb. 1841.

The earliest of all I’ve so far found comes from an article in the July 1837 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger of Richmond, Virginia: “A Dinner on the Plains, Tuesday, September 20th. — This was given ‘at the country seat’ of J. C. Jones, Esq. to the officers of the Peacock and Enterprise. The viands were ‘from fair to middling, we wish we could say more.’”

So the phrase is American, most probably early nineteenth century. But where does it come from? There’s a clue in the Century Dictionary of 1889: “Fair to middling, moderately good: a term designating a specific grade of quality in the market”. The term middling turns out to have been used as far back as the previous century both in the US and in Britain for an intermediate grade of various kinds of goods — there are references to a middling grade of flour, pins, sugar, and other commodities.

Which market the Century Dictionary was referring to is made plain by the nineteenth-century American trade journals I’ve consulted. Fair and middling were terms in the cotton business for specific grades — the sequence ran from the best quality (fine), through good, fair, middling and ordinary to the least good (inferior), with a number of intermediates, one being middling fair. The form fair to middling sometimes appeared as a reference to this grade, or a range of intermediate qualities — it was common to quote indicative prices, for example, for “fair to middling grade”.

The reference was so well known in the cotton trade that it escaped into the wider language. Some early figurative appearances in newspapers directly reflect the market usage:

Twenty-five cents a line, then, may be quoted as the present commercial value of good poetry ... fair to middling is probably more difficult of sale.

New York Daily Times, 29 May 1855.

I have only the opinions of some who patronized her entertainments, who profess to be judges of such things. Verdict, as the Price Current says, “fair to middling with downward tendency.”

The Wabash Express (Terre Haute, Indiana), 18 May 1859.

The figurative term starts to appear in Britain in the 1870s, but early examples are all in stories imported from across the Atlantic. Even that seemingly most home-grown British composition, Austin Doherty’s Nathan Barley: Sketches in the Retired Life of a Lancashire Butcher of 1884, written in local dialect, includes it in the speech of an old school fellow who had emigrated and made his money in Michigan. So it was known but labelled as an Americanism. It took until the twentieth century for it to begin to be used unselfconsciously.

4. So help me Hannah

Q From Jon S of Mississippi: By any chance do you know the origin of the American expression, So help me Hannah? It used to be heard more often in days gone by, and people today may have never heard of it, but it’s an old saying that I cannot find the origin of.

A I can’t provide a definite origin but I can give some pointers.

Hannah, as a personal name, sometimes with the spelling pronunciation “Hanner”, has been used in the US in various colloquial sayings since at least the 1870s. They include that’s what’s the matter with Hannah, indicating emphatic agreement, of which John Farmer wrote disparagingly in his Americanisms of 1889, “A street catch-phrase with no especial meaning. For a time it rounded off every statement of fact or expression of opinion amongst the vulgar.” Another, since Hannah died, was a reference to the passage of time.

The earliest on record is he doesn’t amount to Hannah Cook, later often abbreviated to he doesn’t amount to Hannah and also appearing as not worth a Hannah Cook.

Mr. Sweeney rose again to explain the mysteries of printing ballots the evening before election, and added that the acceptance or rejection of the investigating Committee’s report “didn’t amount to Hannah Cook,” because it made no recommendations.

Boston Daily Globe, 9 Sep. 1875.

This early appearance in a Boston newspaper supports the general opinion that it’s of New England origin. John Gould suggested in his Maine Lingo of 1975 that it derived from seafaring: “A man who signed on as a hand or cook didn’t have status as one or the other and could be worked in the galley or before the mast as the captain wished. The hand or cook was nondescript, got smaller wages, and became the Hannah Cook of the adage.” The story sounds too much like folk etymology to be readily swallowed.

So help me Hannah is a mildly euphemistic form of the oath so help me God, which starts to appear in print in the early twentieth century. Hannah here seems likely to have been borrowed from one or other of the earlier expressions. It became widely used in the 1920s and 1930s.

“By hell, Chief,” he drawled, drawing a huge clasp-knife from his

pocket, “I been grazin’ on this here Alasky range nigh on to twenty

yars, and so help me Hannah, I never did find a place so wild or a

bunch o’ hombres so tough but what sooner or later all hands starts

a-singin’ o’ the female sect.”

Where the Sun Swings North, by Barrett Willoughby, 1922.

After the Second World War, the American firm Hannah Laboratories produced a salve with the name So help me Hannah. Some people have pointed to this as the origin of the expression, though the firm was, of course, merely exploiting a phrase that had long since become part of the common language.

5. Elsewhere

OED history revealed. I have this week spent much time that I should have been devoting to other things in dipping into Peter Gilliver’s scholarly work The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary. It tells the story from its prehistory, through the long and often difficult process of creating the first edition, its supplements and the second edition, to the early stages of the research into OED3. Uniquely among OED historians he is an experienced lexicographer, who has worked on the OED and other Oxford dictionaries since 1987. His heavily footnoted text is a testament to the depth of his decade of investigation; it’s not for the casual reader but will repay anyone with a serious interest in the story behind one of Britain’s greatest treasures. (Hardback, already out in the UK, £40; to be published in the US on 25 October at $65.)

Slang dictionary goes online. While we’re on national treasures, it’s timely to mention Green’s Dictionary of Slang (reviewed by me in 2010), a magisterial three-volume creation by Jonathon Green, which one writer has called the OED of slang (53,000 headwords, 110,000 slang terms, 410,000 examples of usage). The work is online from 12 October at https://greensdictofslang.com/ with comprehensive search facilities. If you wish only to check a headword, an etymology and a definition, the site is free; if you want to access the full work and timeline of development, you can take out an annual subscription, currently £49.00 ($65.00) for single users, £10.00 ($15.00) for students. Just like the OED, online publication means that the work is continually being updated; nearly 30% of the print book has been revised, augmented and generally improved, and as just one example, early quotations for various senses of dope which I unearthed while writing my piece of 6 August and sent to Jonathon have already been incorporated into the entry.

Origin of slang. What is perhaps most interesting about slang is that the origin of its name has long been debated and still isn’t firmly established. Some experts have argued for a link to the English verb sling, to throw, with the implication that it’s disposable or throw-away language. Modern dictionaries say this is improbable but have nothing to put in its place, falling back on phrases such as “origin unknown”. In 2008, in his Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology, Professor Anatoly Liberman suggested it came from another sense of slang, a narrow strip of land, which he linked to various words of Scandinavian origin that imply a group of travellers, tramps or hawkers. He argued that the progression of sense is “A piece of land -> those who travel about this territory (first and foremost, hawkers) -> the manner of hawkers’ speech -> low class jargon, argot.” Prof Liberman has this week repeated his argument in his Oxford Etymologist blog. Not everyone is as yet convinced.

6. Joe Soap

Q From Steve Campbell: My dear old mother would occasionally use the expression Who do you think I am, Joe Soap? We migrated to Australia from the Old Dart in 1951 and I’ve never heard it used by Australians. What is its origin and is it still in use in the UK?

A It remains moderately common in Britain but its meaning has shifted since your mother learned it. She would have had in mind a stupid or naive person, one who could be easily put upon or deceived. These days it refers to a typical individual, the archetypal person in the street.

The full judgement will be published in a week or two and the ordinary Joe Soap will take hours to read it and understand.

Daily Mirror, 9 Sep. 2015.

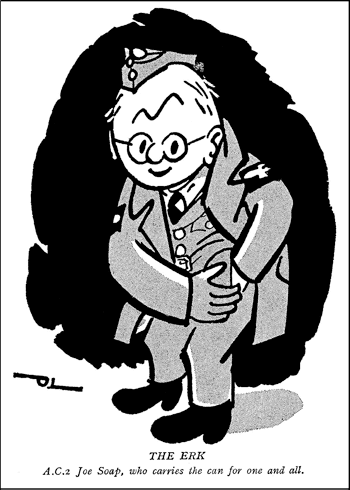

An early wartime use, in an illustration by David Langdon in Cyril Jackson’s It’s a Piece of Cake — RAF Slang Made Easy of 1943. The text reads “A.C.2 Joe Soap, who carries the can for one and all.”

This sense is now known outside the UK, especially in North America.

Your mother’s sense is usually regarded as services slang from the Second World War, most often associated with the Royal Air Force:

Joe Soap was the legendary airman who carried the original can. He became a synonym for anyone who had the misfortune to be assigned an unwelcome duty in the presence of his fellows, or to be temporarily misemployed in a status lower than his own. “I’m Joe Soap,” he would say lugubriously, and I’m carrying the something can.”

Royal Air Force Quarterly, 1944. “Something” may be read as a polite substitute for a more forceful epithet. See here for carry the can.

The term certainly became popular during the war but there’s evidence it was known earlier in the naive sense:

I ain’t no Joe Soap to go a-believin’ of all their yarns.

Blackwood's Magazine, 1934. The writer who quoted this added, “Who Joe Soap was I have never discovered”, which suggests it wasn’t then widely known.

What might be an earlier services connection is the song Forward Joe Soap’s Army, which featured in Joan Littlewood’s musical Oh What a Lovely War and in the film made of it. Despite claims that the songs in the play were authentic First World War creations, I can find no reference to it before the play was first performed in 1963.

However, it wouldn’t have been an anachronism, since the phrase can be traced to the nineteenth century as a generic name for someone unknown, or a pseudonym that was adopted by somebody wanting to stay anonymous.

A man whose real name is unknown, but who is known in the district as “Joe Soap,” had on Tuesday evening crossed a field near Meltham, to get to Bingley Quarry, but in the dusk, mistaking his position, he fell into the quarry, and was killed.

Leeds Times, 21 Sep. 1878.

Witness then went across the road to him and told him to be quiet, and defendant who was using very bad language, put on his coat and got into his trap. Witness then asked him his name and he said “Joe Soap, that will do for you.”

Chepstow Weekly Advertiser, 13 Apr. 1907.

Nobody knows for sure where this generic name comes from.

The first part has been widely used to refer to an ordinary person — Joe Bloggs, Joe Blow, Joe Sixpack, Joe Average, ordinary Joe, Joe Doakes, Joe Public — there are lots of examples, though most of them originate in North America. Joe was noted in Britain as a generic term in 1846, albeit in a different sense, when it appeared in The Swell’s Night Guide: “Joe, an imaginary person, nobody, as Who do those things belong to? Joe.” The unknown-person sense of Joe Soap might have come from it.

It is usually assumed that the second part is rhyming slang for dope, a stupid person, though this would have been improbable in the nineteenth century. Though a couple of examples of dope with that meaning are recorded from the dialect of Cumberland in the 1850s, it wasn’t then widely known in Britain. In that sense it was imported later from North America.

My thanks to Peter Morris, Garson O’Toole and Jonathan Lighter of the American Dialect Society for their contributions to revising this article.

7. Sic!

• A confusing headline in the Boston Globe online on 11 August left readers, among them Bart Bresnik, wondering who was searching for whom: “Woman found abandoned in hospital as baby searches for mom.”

• The website of a hotel in California left Michael Boydston feeling it may be providing more than he was looking for: “Nestled in your opulent guest room with luxurious bedding and special amenities, the Drisco’s thoughtful staff will be there to anticipate your needs and carry out your wishes.”

• Department of too much information: “Portis told us everything. Then Princess Cire told us the rest.” (Behind the Throne, by K B Wagers, 2016).