Newsletter 929

05 Nov 2016

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

It was a pleasure to learn on Tuesday that Randy Cassingham, who writes the This Is True newsletter, had included World Wide Words in his Top 11 Hidden Gems of the Internet suggested by his subscribers. He described the site as “a treasure trove of past articles: the kind of site where you pop in ... and don’t look up again for hours.” Check out the others here: http://wwwords.org/hdngms. A special welcome to the new subscribers who joined through consulting the list.

The piece below about the expression happy as a sandboy is a substantial revision with new information of one first written in 2002.

2. Fizgig

Today — 5 November — is one of those periodic celebrations of failure we Brits so much enjoy, in this case the inability of Guy Fawkes to blow up Parliament on this day in 1605. For the four centuries since, the day has been celebrated with fireworks and bonfires.

One such firework was the fizgig, an unspectacular device that hissed rather than banged, for which reason it has also been called a serpent; a conical form has the name volcano. A English poet once compared a man to one:

Northmore himself is an honest, vehement sort of a fellow who splutters out all his opinions like a fiz-gig, made of gunpowder not thoroughly dry, sudden and explosive, yet ever with a certain adhesive blubberliness of elocution.

Letter from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Thomas Poole, 16 Sep. 1799.

Not to be confused with the fizzgig, the friendly monster from the Jim Henson and Frank Oz film The Dark Crystal.

Fizgig in the sense of the firework is now quite dead, as are most of the other senses that this weirdly catholic word has had. The original was a frivolous woman, fond of gadding about in search of pleasure — an alliterative-minded seventeenth-century man wrote of “Fis-gig, a flirt, a fickle .... foolish Female”. The word was built upon gig, another word that has had many meanings; Chaucer knew it as a fickle woman but Shakespeare considered it to be a child’s top. The first part of fizgig is obscure. It can’t be fizz, effervescence, because that came along much later, probably as an imitative sound. It may be the same word as the obsolete fise for a smelly fart.

Another defunct meaning of fizgig is that of a harpoon, a fish-spear:

Two dolphins followed us this afternoon; we hooked one, and struck the other with the fizgig; but they both escaped us, and we saw them no more.

Journal of a Voyage from London to Philadelphia, by Benjamin Franklin, 1726.

This was sometimes perverted into fish-gig by popular etymology. It has no link with the other senses but derives from the Spanish word fisga for a harpoon.

Fizgig principally survives in Australian slang, where it means a police informer. It turns up first in the 1870s, perhaps as an extension of the female sense, considered stereotypically as dashing about madly and gossiping indiscreetly:

Without their allies — “the fizgigs,” the police seem powerless to trace the authors of the robberies which are now of such frequent occurrence.

Victorian Express (Geraldton, WA), 15 Nov. 1882.

3. Spin a yarn

Q From From Ada Robinson: I came across the phrase spinning a yarn (in the sense of telling a story) recently, and for the first time wondered about its origin. Can you shed light on how the word yarn acquired the second meaning of a tale?

A It’s puzzling because we’ve lost the context.

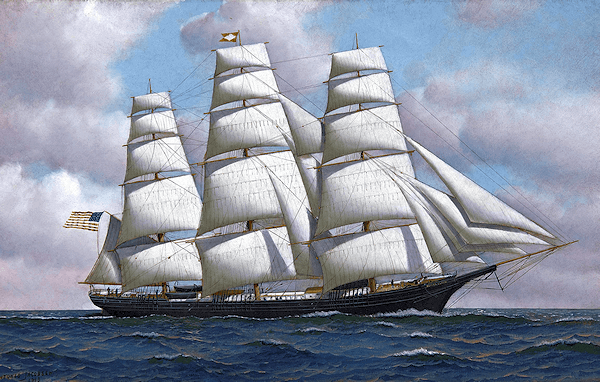

We know that sailors were the first to use spinning a yarn — often in the extended form spinning out a long yarn — to refer to telling a story that described a speaker’s adventures and exploits.

We start to see the expressions in print in the early nineteenth century, though its ultimate origin is unclear. However, we do know that one task of sailors was to make running repairs to the various ropes of the ship — the cables, hawsers and rigging. As with people on shore, yarn was their word for the individual strands of such ropes, often very long. Their term for binding the strands into fresh rope was spinning or to spin out. The next part is a jump of imagination, for which you may substitute the word guess, though I would prefer to call it informed speculation. The task of repair was necessarily long and tedious. We may easily imagine members of the repair crew telling one another stories to make the time pass more easily and that this practice became associated with the phrases.

Many opportunities for yarn-spinning exist here.

By the second decade of the century, the term was being used ashore and became a popular slangy idiom. One appearance was in a jocular report of a police court action in Edinburgh which centred on a sailor who had stolen a milk cart:

When the first witness was put in the box, and had his mouth most oracularly opened, preparing to speak, Jack, twitching him by the collar with his forefinger, caused him at once to descend, and exclaimed — “Avast there; none of your jaw; who wants you to spin out a long yarn?”

The Edinburgh Advertiser, 17 Nov. 1826.

In time, yarn came to refer to the stories. Many must have been exaggerated or bombastic and that sense of something not readily believable still attaches itself to the word. In Australia and New Zealand the word has softened in sense to mean no more than chatting.

4. Chalazion

Peter Gilliver, the eminent lexicographer with the Oxford English Dictionary whose book I mentioned last time, quoted this word in an interview a couple of weeks ago. He said he had found it when a youngster in a children’s dictionary that was full of such unusual words.

I made the mistake of looking for it in Google Books, where I found several works which explained it in terms such as “a common lipogranulomatous inflammation of the sebaceous glands of the eyelids, most often the meibomian glands.” Some works also noted that it’s sometimes known as a hordeolum. In confusion, I visited Dr Gilliver’s wonderful online repository of knowledge, in which chalazion is defined as “a small pimple or tubercule; especially one on the eyelid, a stye.”

Chalazion is the diminutive of Greek chalaza for almost any lump, including a small hailstone and a pimple. The OED helpfully pointed me to its entry for chalaza, which stated that in English it’s a zoological term for “Each of the two membranous twisted strings by which the yolk-bag of an egg is bound to the lining membrane at the ends of the shell.”

The meibomian glands make a lubricant for the eye. Their name isn’t from a classical language but derives from a seventeenth-century German anatomist named Heinrich Meibom. And hordeolum derives from the Latin word for barley grains

The plural of chalazion, should you ever suffer from more than one, is chalazia.

5. In the news

Words of 2016. The annual lexicographical wordfest began on Thursday with a list of topical terms from Collins Dictionary. Its choice for Word of the Year was Brexit, Britain’s exit from the European Union. The term went from nowhere to established part of the language in an extraordinarily brief time. The earliest recorded use may have been the one in The Guardian on 1 January 2012 but it became widely used by the general public only in the early months of this year. The publisher suggests it “is arguably politics’ most important contribution to the English language in over 40 years”. It has spawned many spin-offs, including Bremorse for the regret by people who voted to leave but realise they made a mistake and would like to Bremain or Breturn. Other words in the Collins topical list are hygge, a suddenly fashionable and much written about Danish concept of creating cosy and convivial atmospheres that promote wellbeing, and uberization, derived from the name of the taxi firm Uber, for the adoption of a business model in which services are offered on demand through direct contact between a customer and supplier, usually via mobile technology.

Fount of fonts. Subscriber Bart Cannistra came across a news item about a new pan-language collection of fonts from Google and Monotype that supports more than 100 scripts and 800 languages in a common visual style. Its name is Noto, which its website says is short for “no more tofu”. It explains that tofu is digital typographer’s jargon for one of those little rectangular boxes that appear when your browser doesn’t have the appropriate font to display a character. The boxes sometimes have a question mark or cross inside them but it’s their rectangular shape that has given them the name, since they reminded some unheralded type designer of the cuboid blocks of tofu.

Not that kind of girl. Readers outside the UK are most likely unfamiliar with the term Essex Girl, which Collins Dictionary defines as “a young working-class woman from the Essex area, typically considered as being unintelligent, materialistic, devoid of taste, and sexually promiscuous.” It’s in the news because two Essex women have begun a petition to have the term stricken from dictionaries because they’ve had enough of derogatory references. They have been criticised for starting the petition because it only leads to more public mention of the term. The term came to public attention in 1991 with the publication of The Essex Girl Joke Book (typical example: “How does an Essex Girl turn on the light after sex? She opens the car door”), but the stereotype is best known through the long-running ITV programme The Only Way is Essex. The OED has already refused to remove the term, on the excellent grounds that it’s part of our living language.

6. What am I? Chopped liver?

Q From Mary Clarke: Your piece on Joe Soap made me think of the phrase What am I? Chopped liver? Is this a New York expression or a Jewish expression? I ask this because we seem to eat more chopped liver here than anywhere else and because one of the nicest compliments I’ve ever received was from a friend who said my chopped liver was better than her Jewish grandmother’s.

A This takes me back. In November 1999, when this newsletter had already reached issue 167, I mentioned that a reader had asked about this but as it was unfamiliar to me, I asked for elucidation. The resulting flood of emails was overwhelming. Though I summarised the results the following week, I realise now that I never went into detail, nor posted anything on my website.

A dish of chopped liver — fried chicken livers with eggs, spices and, if you’re being really traditional, schmaltz and gribenes (respectively rendered chicken fat and fried chicken skin as a form of crackling) — is common at Jewish celebratory meals. It’s also a standard dish in New York Jewish delicatessens. But it’s inexpensive and never a main dish, wherein lies the core of the idiom. Sol Steinmetz, the American linguist and Yiddish expert, explained that “Chopped liver is merely an appetizer or side dish, not as important as chicken soup or gefilte fish. Hence it was used among Jewish comedians as a humorous metaphor for something or someone insignificant.” Robert Chapman argued in his Dictionary of American Slang that the idiom originated in the 1930s in this sense.

Early in its development a negative reference to chopped liver developed, which instead suggested something excellent or impressive. It parallels another American idiom, that ain’t hay. The idiom appeared in various forms, such as it ain’t chopped liver, that’s not chopped liver, and it’s not exactly chopped liver. The first of these forms is noted by Jonathan Lighter in his Historical Dictionary of American Slang from a Jimmy Durante television show in 1954. It must surely be older. This is another version, from a little later:

Some of the critics put it right up there with “My Fair Lady.” Even before it lifts the curtain there is a million dollars in advance orders and this as the boys say is not chopped liver ...

The Victoria Advocate (Victoria, Texas), 8 Mar 1959.

The form that you mention appears in the historical record a few years later still. Somebody exclaiming What am I? Chopped liver? is expressing annoyance at being thought unworthy of attention: “What about me? Why am I being ignored? Don’t I matter?”

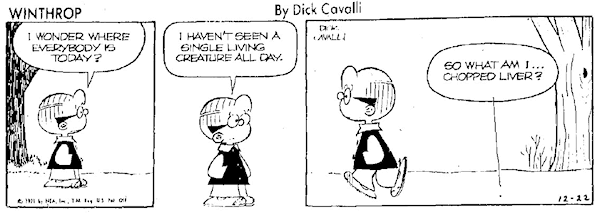

The earliest example that I’ve come across is this, in a cartoon strip in The Provo Herald of Utah, dated 22 December 1971.

It could be New York Jewish. It has the right cadence for a Yiddish exclamation and chopped liver, as we’ve seen, is an archetypal Jewish dish. And the experts suggest it grew out of a catchphrase of comedians in the Borscht Belt of the Catskill Mountains patronised by Jewish people from New York City. But there’s no certain connection. What is clear that it filled a need and that even by its earliest written appearances it had already reached places well away from centres of Jewish life.

7. Happy as a sandboy

Q From Niki Wessels, South Africa; a related question came from Robert Metcalf in Singapore: Our family recently discussed the expression happy as a sandboy, and wondered where and how it originated. My dictionary informs me that a sandboy is a kind of flea — but why a boy, and why is it happy?

A Let me add an explanatory note to your question, as many readers will never have heard this saying. It’s a proverbial expression that suggests blissful contentment:

Made me think it might be a good idea to mark the occasion. Nothing too big, you understand. Not looking for fireworks and flags or anything. I’m a modest man with modest needs. Give me a bit of cake, maybe some tarts, throw in a couple of balloons and I’m happy as a sandboy.

Bristol Evening Post, 11 Aug. 2015.

It’s mostly known in Britain and Commonwealth countries. An older form is as jolly as a sandboy, which is now rarely encountered. The first examples we know about are from London around the start of the nineteenth century.

A sandboy in some countries can indeed be a sort of sand flea, but this isn’t the source of the expression. Incidentally, nor is there a link with the sandman, the personification of tiredness, which came into English in translations of Hans Christian Andersen’s stories several decades after sandboy.

The sandboys of the expression actually sold sand. Boy here was a common term for a male worker of lower class (as in bellboy, cowboy, and stableboy), which comes from an old sense of a servant. It doesn’t imply the sellers were young — most were certainly adults — though one early poetic reference does mention a child:

A poor shoeless Urchin, half starv’d and suntann’d,

Pass’d near the Inn-Window, crying — “Buy my fine Sand!”

The Rider, and Sand-Boy in the Hereford Journal, 13 Jul. 1796. The title contains the earliest known reference to a sandboy. The poem was unattributed but is almost certainly by William Meyler of Bath. Note that to be described as suntanned wasn’t then a compliment; it implied an outdoor worker of low class.

The selling of sand wasn’t such a peculiar occupation as you might think, as there was once a substantial need for it. It was used to scour pans and tools and was sprinkled on the floors of butchers’ shops, inns and taprooms to take up spilled liquids. Later in the century it was superseded by sawdust.

Henry Mayhew wrote about the trade in his London Labour and the London Poor in 1861. The sand was dug out from pits on Hampstead Heath and taken down in horse-drawn carts or panniers carried on donkeys to be hawked through the streets. The job was hard work and badly paid. Mayhew records these comments from one of the excavators: “My men work very hard for their money, sir; they are up at 3 o’clock of the morning, and are knocking about the streets, perhaps till 5 or 6 o’clock in the evening”.

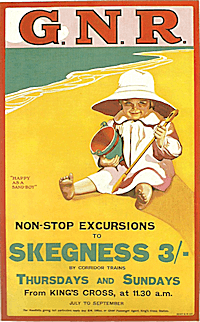

By 1907, when this railway poster appeared, the small boy on the beach could be humorously described as happy as a sandboy with no hint of the real origin of the expression.

Their prime characteristic, it seems, was an inexhaustible desire for beer. Charles Dickens referred to the saying, by then proverbial, in The Old Curiosity Shop in 1841: “The Jolly Sandboys was a small road-side inn of pretty ancient date, with a sign, representing three Sandboys increasing their jollity with as many jugs of ale”. An early writer on slang made the link explicit:

“As jolly as a sand-boy,” designates a merry fellow who has tasted a drop.

Slang: A Dictionary of the Turf, the Ring, the Chase, the Pit, of Bon-tom, and the Varieties of Life, by John Badcock, 1823. To have become an aphorism by this time, sandboy must surely be older than the 1796 poem quoted above.

Quite so. But I suspect that the long hours and hard work involved in carrying and shovelling sand, plus the poor returns, meant that sandboys didn’t have much cause to look happy in the normal run of things, improving only when they’d had a pint or two. Their regular visits to inns and ale-houses presented temptation to a much greater degree than to most people and it has also been suggested that they were often paid partly in beer.

So sandboys were happy because they were drunk.

At first the saying was meant ironically. Only where the trade wasn’t practised — or had died out — could it became an allusion to unalloyed happiness. To judge from the answers to a question about its origin in Notes & Queries in 1866, even by then its origin was obscure.

8. Sic!

• A headline on the Hertfordshire Mercury site on 14 October — “Tributes paid to Waltham Cross Labour councillor who was a ‘real character’ following his death” — led Ross Mulder to wonder what the man was like during his life.

• If you’re going to do something, do it properly. Ted Dooley found this news in an email from the Minneapolis Star Tribune on 7 October: “Ryan D. Petersen, 37, was convicted Friday morning of first-degree premeditated murder for fatally shooting a law clerk eight times earlier this year.”

• A puzzling statement from The Age of Melbourne of 10 October about the illegal demolition of a heritage-listed pub was submitted by Susan Ross: “A petition law students started this week demanding the pub be rebuilt by Tuesday afternoon had more than 5000 signatures.” A comma after “rebuilt” might have helped.