Newsletter 726

05 Mar 2011

Contents

1. Feedback, notes and comments

Phrop Lawrence Krakauer e-mailed: “It seems to me that you applied this term to two entirely different things. A phrase like we must have lunch sometime is not ambiguous, it’s just insincere. But thank you for sending your book — I shall lose no time in reading it is intentionally ambiguous. Perhaps we need different words for these two types of phrop.” Perhaps, Julane Marx suggests, we might call the latter a malaphrop. The first sense is the original, as I noted in the piece; the other is an example of what some have described as autoantonymic or Janus phrases. The biggest group of these are humorously ambiguous job references. Readers sent in examples, such as “You’ll be lucky if you can get this man to work for you”. There’s even a book of them, The Lexicon of Intentionally Ambiguous Recommendations or LIAR for short. Guy Aron remembered the famous Pears soap advertisement from 1893 onwards, based on a cartoon in Punch in 1884 by Harry Furniss, in which a filthy tramp was writing to the firm: “Dear Sirs, two years ago I used your soap. Since then I have used no other.”

That’s all she wrote An excellent find by Michael Templeton takes its written history back two years to an article about a cockfight in the April 1942 issue of H L Mencken’s American Mercury: “‘That’s all she wrote!’ gleefully called out a fan, before crossing the pit to collect a fifty-dollar bet.” He also found a song by Ernest Tubb, the Texas Troubadour, entitled That’s All She Wrote, also from 1942. Confusingly, that is widely attributed to Jerry Fuller in 1950, though as he was 12 at the time, he would have had to be precocious to write about being dumped by his girl. I posted these findings on the American Dialect Society discussion list; within hours Garson O’Toole had found three examples of that’s all she wrote in the Atlanta Daily World from June and August 1942. As all these examples are from civilian contexts, the prevailing view that the idiom is from servicemen being dumped by Dear John letters is no longer sustainable. My guess is that the immediate source will turn out to be Ernest Tubb’s song, which surely must have been performed on radio before 1942 and which popularised it.

2. Weird Words: Erumpent/ɪˈrʌmpənt/

Stifle your delight, Harry Potter fans. We’re not discussing that elephant-like beast, whose over-sensitive horn exploded in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

It’s a good name for the animal, though, with its hints of “erupt” and “trumpet”, and its true meaning, of something bursting forth, might describe an explosion. A few writers have borrowed the word to salt their prose: “The musicians added to the erumpent revelry with a sprightly semi-martial tune”, wrote Alan Dean Foster in Icescape. Better was the almost poetic “Snowdrops are erumpent in the dreary winter landscape”, which the gardener Lia Leendertz recently wrote in The Guardian, because it locates the word nearer to its true home.

Erumpent

Botanists and biologists, the only people who employ it at all regularly, commonly bury it in the undergrowth of dense technical descriptions: “Pseudothecia mainly epiphyllous, in dense clusters, immersed but becoming erumpent”. It has most often been used to refer to the fruiting bodies of fungi, which in their season are notably erumpent.

It’s from the Latin verb rumpere, to break out. That’s the source of several much more common English adjectives and verbs that end in -rupt, notably abrupt, erupt and interrupt, as well as the outstandingly rare rumpent — the Oxford English Dictionary defines this last word as an application for breaking a swelling, but it has only one example of it and doesn’t explain further.

3. Wordface

Bruce Thorpe tells me that the term munted has been widely heard in New Zealand in the past ten days in reference to the Christchurch earthquake. A typical comment is “our neighbour’s house is munted”, meaning that it has been totally destroyed. This sense is confined to New Zealand. In Australia it’s known in the broader sense of something deeply ugly or unpleasant. Teen slang in the UK uses it as a derogatory term for an unattractive woman, who may be a munter. In all three countries it also means being very drunk or out of it on drugs. The word is 1990s slang but nobody seems to have much idea where it comes from.

4. Questions and Answers: Limerick

Q From James Grainger: It has for many years puzzled me that the verse form should be known as a limerick. Can you help?

A Your puzzlement has long been shared by historians of language.

The title page of the American third edition of

Lear's first nonsense book, 1861

The nineteenth-century illustrator and poet Edward Lear is closely associated with the form. But he didn’t invent it. He borrowed it from examples that he discovered in a book of 1822, Anecdotes and Adventures of Fifteen Gentlemen (a couple of other books containing examples appeared two years before). One verse gave Lear the idea of writing limericks to accompany his illustrations for children:

There was a sick man of Tobago

Who lived long on rice-gruel and sago;

But at last, to his bliss,

The physician said this —

“To a roast leg of mutton you may go.”

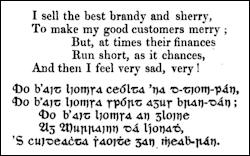

Examples of the verses, in English

and Gaelic, from John O’Daly’s book

The form is often claimed to be older. Modern books about Ireland link it to the eighteenth century Filí na Máighe, Gaelic poets of the Maigue, based in a pub in Croom, County Limerick. Two members of the group were Seán Ó’Tuama and Aindrias MacCraith, who jousted in verses with limerick metre. These were translated into English by the poet James Clarence Mangan, and appear in both languages in John O’Daly’s The Poets and Poetry of Munster of 1850. This was before Edward Lear’s work became widely known; he became popular only after his Book of Nonsense of 1846 was republished in 1861.

Neither Lear nor O’Daly nor the authors of the books of the early 1820s called these poems limericks. The first known appearance of that name is in a letter dated 1896 by the artist and illustrator Aubrey Beardsley.

In O’Daly’s book the verses are headed by “Air: The Growling Old Woman”, indicating that they were intended to be sung, not recited. In 1898, a contributor to the scholarly journal Notes and Queries expanded on this: “Certain it is that a song has existed in Ireland for a very considerable time, the construction of the verse of which is identical with that of Lear’s”. He went on to describe a custom at convivial parties:

One member of the party started a verse, and when he had concluded the whole assembly joined in the chorus. Then the next performer started a second verse, and so on until each one had contributed a verse; repetitions were not allowed, and forfeits were extracted from those who could not fulfil the conditions. This meant that each one had to supply an original verse of his own.

Notes and Queries, 9th Series, Vol 2, 10 December 1898.

The writer adds that the chorus consisted of the repeated lines “Will you come up, come up? / Will you come up to Limerick?” Stephen Goranson, a librarian at Duke University, North Carolina, has found a related reference from the other side of the Atlantic from 18 years earlier:

There was a young rustic named Mallory, who drew but a very small salary. When he went to a show, his purse made him go to a seat in the uppermost gallery. Tune, wont you come to Limerick.

St John Daily News (New Brunswick), 30 Nov. 1880.

The tune is presumably the traditional jig often called Will You Come Down To Limerick (“up” and “down” seem to be interchangeable or omitted at will). It appeared under that title in the famous collection Music of Ireland by Captain Francis O’Neill, published in Chicago in 1903.

Stephen Goranson argues on the basis of this item that the limerick was named in the US, with the chorus of the jig based on a Civil-War era slang phrase, come to Limerick or bring to Limerick, meaning submit to authority, which he suggests might be a reference to the Civil War in Ireland, concluded at Limerick in 1691. He has as yet been unable to confirm this and I’m sceptical. (I’m going to write about this in more detail later.)

To summarise, we have two possibilities for the origin. The obvious one is that the name comes from the verses written by the men of County Limerick. But if that’s so, why didn’t the name appear much earlier than it did? I’m sure they only became at all known after limerick had entered the language and people began to seek its source, seizing on the Filí na Máighe without looking too deeply into dating. The other possibility is that the name was taken from the chorus or title of the jig. As it was known on both sides of the Atlantic, and the earliest examples of the term are from the UK, it is most likely to have first appeared in Britain. This remains the more probable suggestion.

5. Sic!

• The Camden New Journal of London, dated 24 February, featured an article on a sit-in at the Barclays bank in Tottenham Court Road, which got Julia Clarke’s attention for the wrong reason: “Organised by UK Uncut, campaigners claim the multinational bank only pays a slither of its national profits in corporation tax, amounting to 1 per cent.” Free association test: “Banker?” “Slither!”

• A mixed metaphor appeared in the Daily Telegraph on 25 February. Anthony Massey found it in a piece claiming that cuts in UK defence spending would make it difficult to mount even a small-scale operation in future. An officer was quoted: “We have cut our cloth very small and if we bit off more than we could chew we would be in trouble.”

• The Morning Sentinel of Waterville, Maine, carried a report on 28 February which John Sweney read. It concerned a parish letter sent by the local pastor, Father Joseph Daniels, that detailed cutbacks in services due to a shortage of priests: “Daniels also said the parish will need to eventually grapple with a longer-term problem: the number of shrinking Catholics attending church in the Waterville area.”

• Stu Wrenn and Laurie Camion spotted a photo caption in a story on the Daily Mail website on 2 March: “Floundering tyrant: Gaddafi, pictured last night as he made a series of bizarre statements, has had billions of pounds worth of his assets frozen along with his daughter and four sons”.