Newsletter 778

17 Mar 2012

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Etiquette Following up my piece about this word last time, Marc Naimark noted: “Ticket has re-entered French from English. It means a bus, tram or subway ticket. A regional rail ticket could be either billet, which is probably the official term, or ticket, used by most people.” Claude Baudoin added, “The French have also borrowed label (pronounced like la belle) for a seal of approval by some quality control organization. So you can have a label de qualité or simply label that tells you that a certain food item is organic, that an appliance is energy-saving, etc. This criss-crossing of words and meanings is really interesting.”

Ambulance Anthony Massey wrote in similar vein about this word, also discussed last week. “In many European languages, ambulances have lost their wheels, if they ever had them, and have become buildings. So in Dutch, German and Danish, Ambulatorium means a hospital outpatients department. In German the department might also be referred to as Ambulanz or Spitalambulanz. In Danish I have found geriatrisk ambulatorium, a geriatic outpatients facility. In Polish, Ambulatorium could mean the outpatients department or the accident and emergency department, but always part of a hospital. In Serbian and Croatian (as we now call the language formerly known as Serbo-Croat) Ambulanta tends to mean a clinic or infirmary, but again somewhere which can treat emergency cases. In rural areas, such as part of Kosovo which I visited a few years ago, ambulanta would equate to a UK cottage hospital. The Albanian population would probably have preferred to call it a spital, the Albanian for hospital. But as this one had been built by the Serbs, the sign said ambulanta, and the locals told me in their best English (much better than my Albanian!) that they were taking patients ‘to the ambulance’, meaning ‘to the hospital’.”

2. Weird Words: Festucine/ˈfɛstjʊsaɪn/

The 4,000-year-old epic of the mighty warrior Gilgamesh includes a description of distant mountains that has been translated as

And see! they change their hues incarnadine

Obviously enough, festucine is a colour, though not one that often appears on colourists’ charts. That might be because nobody is quite sure what hue it really represents. As it is from Latin festūca, a straw, it seems reasonable to argue that it’s a yellowish colour — some reference books indeed assert that it is. But as festūca was also applied to any grass-like plant, others suggest it’s a greenish colour or one partway between green and yellow.

It was invented by the physician and author Sir Thomas Browne in his 1646 encyclopaedic work, Pseudodoxia Epidemica. He certainly meant by it a shade of green: “Herein may be discovered a little insect of a festucine or pale green, resembling in all parts a Locust, or what we call a Grashopper.”

It’s been used rarely. I was startled to come across this example in an old newspaper, an extended high-flown essay on a visit of a blue jay to a local park, whose prose, however purple, doesn’t include it as a colour term:

It looked upon the gazing throng and with abandon cast down the festinative fervor of its song, that festucine song, thin as the reddening sting of ripe wine and as elfinly vivacious as the querulous flight of oriental melodies maddened by the flame of hashish or intoxicated by the love-hungered stress of lutes.

Hagerstown Mail (Maryland), 10 Oct. 1902. Festinative isn’t in any reference work that I’ve consulted, but festinate and its relatives mean hurried or hasty.

These days, festucine is best known among biochemists; it’s the name of an alkaloid. It was extracted by S L Yates and H L Tookey in 1965 from a fungus growing on a grass called tall fescue, botanical name Festuca arundinacea, which demonstrates that fescue is ultimately also from Latin festūca. I guess that their festucine was inspired by the plant’s botanical name rather than its colour.

3. Wordface

In formation Some adjectives end in -iform, meaning to have a specified form, a suffix English has borrowed from Latin forma, a mould. Most of us know cruciform and uniform. Less familiar ones include aviform, like a bird, and vermiform, like a worm. Last Sunday’s Observer discussed symbols which our distant ancestors were said to have painted on cave walls in France and Spain alongside the better-known representations of animals. The article gave words describing a number of symbols. For example, tectiform accompanied one with an inverted V shape on top, which is appropriate because it means “like a roof” (Latin tectum); reniform captioned a kidney shape (a relative therefore of renal); if you turn one symbol 90 degrees it looks a little like a ladder, hence it was said to be scalariform (from Latin scālāris, like a ladder); unciform referred to a hooked symbol (Latin uncus), a term otherwise mainly used in anatomy; a symbol with a central line and a series of short lines extending from one side of it at right angles was given the adjective pectiform (the Oxford English Dictionary doesn’t admit this one, but it’s from Latin pecten, a comb).

Time machine not supplied Jargon often defeats me. An item in my newspaper on Wednesday reported that because of the loss of legal aid for many people in the UK, ministers were pushing for people to take out BTE insurance. The item explained that this stands for “Before The Event”. Hang on a moment, isn’t all insurance supposed to be taken out before the event?

4. Questions and Answers: Nerd

Q From Ros Hirch: A friend posted on Facebook that, according to dictionary.com, Dr Seuss coined the word nerd. According to the best available evidence I have, he was the first to print it, in If I Ran the Zoo; however, one year later, Newsweek printed an article in which it described nerd as a popular slang term. It seems unlikely to me that it could go so quickly from Dr Seuss to teen slang, especially considering that I doubt many teens would be reading Dr S, let alone quoting him. Aside from a lot of stories about acronyms and ne’er-do-wells, I can find no definitive answer. Do you have any insights?

A That’s an excellent summary of one of the puzzles surrounding the word. Nerd has become firmly established in the language since its first appearance in print a little over half a century ago but we don’t know enough to be sure where it comes from. The Oxford English Dictionary says “Origin uncertain and disputed”.

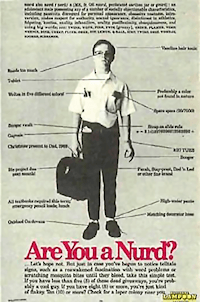

It’s worth noting that nerd (also nurd) has evolved in meaning. Early on, it meant a dull, unattractive, or offensive person. The associations with obsessive technical expertise and fussy dressing (remember nerd pack for a pocket protector?) only came along in the 1970s — illustrated in the National Lampoon’s “Are you a Nurd?” poster of 1977 (see right). Compare and contrast geek, which once had similar associations (if you disregard the stories about biting the heads off live chickens) but has largely been rehabilitated. Geeks are intelligent, hugely knowledgeable about a technical subject but able to get ahead in life (Time had a headline in 1995: “The Geek Shall Inherit the Earth”). Nerds retain an idiot-savant association of being obsessively good at one thing but poor at anything else. Nerds are geeks with no social skills.

The two earliest appearances of nerd, the two you mention, are these:

And then, just to show them, I’ll sail to Katroo And bring back an It-Kutch, a Preep and a Proo, A Nerkle, a Nerd and a Seersucker too!

If I Ran the Zoo, by Dr Seuss, 1950.

Nerds and Scurves: In Detroit, someone who once would be called a drip or a square is now, regrettably, a nerd, or in a less severe case, a scurve.

Newsweek, 8 Oct 1951.

The Dr Seuss origin might be considered confirmed by these, but as you say, a shift from a work for young children to a fashionable teenager term is unlikely to have happened so quickly.

Several other theories have been proposed. One is that it’s short for the Northern Electric Research and Development Laboratories, part of a power utility of Ontario, not so far from Detroit. But the laboratory wasn’t given that name until 1959. As one early spelling was nurd, another suggestion is that it’s a modified or rhyming-slang form of turd. That’s very unlikely.

In 1938, the ventriloquist Edgar Bergen created a new addle-pated country-bumpkin dummy to accompany his suave top-hatted Charlie McCarthy and gave it the name Mortimer Snerd. It’s been argued that Dr Seuss may have subconsciously had this in mind. This source is dismissed by etymologists, but I have come across a few instances of somebody being nicknamed Snerd in the years before nerd was first recorded.

There’s also knurd, which is drunk backwards. The Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute usually gets a mention here, since there are persistent reports that the term was in use there in the 1950s. The joke is one that might have turned up at any time and a version of it is recorded in John Camden Hotten’s Dictionary of Modern Slang of 1859. It also appears in Henry Mayhew’s London Life and the London Poor of 1851 in the spelling kanurd (which suggests the k wasn’t then silent); it seems to have been a popular bit of back slang at this time. Readers of Terry Pratchett know he reinvented knurd in his Discworld fantasy story Sourcery as being “as far on the other side of sober as drunk is on the inebriated side”.

We can’t point to the British English nerk or nurk as being its source because the experts are sure that it’s a blend of nerd and berk, the latter being an abbreviated form of the euphemistic rhyming slang Berkshire Hunt.

It would be impossible — or at least deeply unwise — to support a claim for any of these words being the direct source. My suspicion is that there’s something about the combination of sounds that we conventionally spell nerd that causes it to be reinvented from time to time as a term of disparagement. Perhaps this is because it reminds us of a growl of disgust, disapproval or negation. Bergen surely named his dummy Snerd because of the adverse image that it conjured up. It may be worth recording that English dialect once had knurt for a man who was oafish or stunted in growth and gnarr for peevish fault-finding.

As so often, matters turn out to be more complicated and obscure than those in love with a simple story or obvious explanation will be happy with. But that’s life, or at least etymology.

5. Sic!

• Pick the sense out of this headline over an article in the Boston Globe of 10 March, seen by Joe Quinton and Vance R Koven: “Walpole firm’s anonymity software aids elicit deals”.

• Similarly for this headline that was seen on AOL News on 9 March by Jim Tang: “Man Killed, Dismembered Dad Kills Self”.

• There’s also the potentially misleading “Man Builds Healing Harp from Stand-Up Wheelchair”, a story on care2.com on 12 March seen by Laurence Horn.

• Miles Irving found this in an article on Dalhousie Castle in the Scotsman on 14 March: “The castle was visited by England’s King Edward I, also known as Longshanks, the Hammer of the Scots, and Oliver Cromwell.”