Newsletter 899

11 Oct 2014

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Habiliments. “Your article on habiliments,” emailed John Walmsley, “brought to mind a word used by my great-uncle (and others of his generation) in the 1970s in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It may still be in use there. My great-uncle referred to one’s underwear as ‘your decibels’. (The spelling is as I heard it at age 10.) Once I started to learn French at school, I assumed that this was derived from déshabillé. I just checked my Chambers Dictionary, which is always strong on the words of my Ulster youth. There I find dishabilles and my schoolboy etymology is confirmed.”

Graham Thomas added, “Habiliments reminded me of a book I read in my youth: My Father in His Dizzerbell by Douglas Hayes. Dizzerbell was the eponymous father’s rendition of the French déshabillé and usually meant his dressing gown, which he wore before donning his clothes for the day.”

Focus! Marni Hancock spotted a typo in my review of Steven Pinker’s new book last time. I wrote “mental effect” when I meant “mental effort”. My typing fingers have a will of their own sometimes. However, readers who suggested kindly that in using focussed in the piece I had suffered a keyboard malfunction were off-track, as doubling the s is standard in British English.

Beta testing. Many thanks to everybody who made useful comments on the draft page. With your help the redesign is now in good shape to be rolled out to the whole site. I hope this will happen next weekend.

2. Immensikoff/ɪˈmɛnsɪkɒf/

I was leafing, if that’s the right word, through a digital copy of an issue of the Strand Magazine, most famous as the publisher of Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories about Sherlock Holmes, when this word almost jumped off the page. It was in a story about a child pickpocket who might have come from the pages of Oliver Twist:

He felt himself much drawn toward a man in an “immensikoff”—a fur-lined overcoat —which was quite the most magnificent garment in the crowd. The large side-pocket of the “immensikoff” gaped invitingly, and, though outside overcoat-pockets were barren vessels as a rule, this was so very easy that nothing could be lost by trial.

A Lucifo Match, by Arthur Morrison; Strand Magazine, 6 Jan. 1909. The title is a play on lucifer, a common term for a match; Lucifo was actually a Spanish conjuror, who was wearing the overcoat. He got the better of the pickpocket (match here is in the contest sense).

This grandiloquent word for a rather fine garment was the accidental invention of one of the most famous music-hall artists of Victorian times, Arthur Lloyd, a Scottish-born comedian and singer who made his name in London with a vast output of self-penned musical numbers. This is the first reference to the song that I know about, in an article about the Winchester Music Hall in London:

Mr. Arthur Lloyd appeared in appropriate costumes, and sang and discoursed in his easy, telling manner as “The Pedagogue,” and “Immenseikoff, or the Shoreditch Toff.”

The Era, 5 Apr. 1868.

When singing Immenseikoff, Mr Lloyd portrayed himself as a “swell” (slang of the time for a fashionable or stylish person of wealth or high social position). His song had this chorus:

Immenseikoff, Immenseikoff

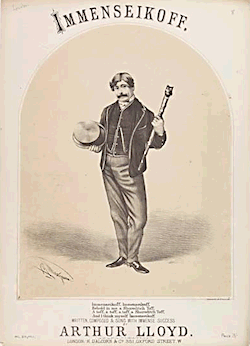

Immenseikoff, or the Shoreditch Toff, a polka with words and music by Arthur Lloyd, published 1860.

Toff is a slang term for a rich or upper-class person. The joke lay in the incongruity of a man from Shoreditch being able to emulate the style and clothing of a well-off person, as Shoreditch was one of the poorest parts of the East End of London. Immenseikoff was presumably a play on the language of Russian Jews who were beginning to settle in the area.

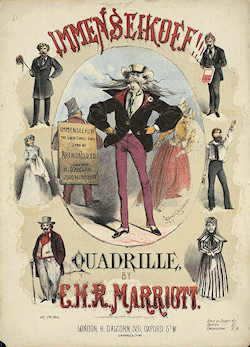

His song became popular (an American visiting London in 1870 remarked that everyone was humming it). His word likewise became well known. In 1869 it appeared in a story in an American newspaper as the name of a Russian giantess in a circus. The same year Charles Marriott, a popular light-music composer of the period, turned Lloyd’s song into a quadrille with the same title.

The word soon lost its second e and came to mean an overcoat. Several decades later it was claimed that this came about because Lloyd wore one when performing the song. However, no contemporary reference exists that I can find and his song doesn’t mention an overcoat. On the cover of the sheet music he’s wearing the “flash” fashion of the time. As the covers of his other songs show him in the costumes he wore to perform them, I suspect that he never wore a overcoat while singing Immenseikoff and that the supposed link was added much later in a misguided effort to explain its meaning. The reason for its adopting this meaning is lost to us.

Immensikoff survived for several decades. Arthur Morrison’s use in 1909 was almost its swansong, though Arnold Bennett employed it in his novel Hilda Lessways two years later.

3. Poach

Q From Ozer Bergman: If I had a poached egg for breakfast, did I have contraband?

A You might guess that we have yet another case of English words of the same spelling and pronunciation that have arrived in the language from different sources. But that may not be true in this case. Bear with me, it’s complicated.

The word meaning to cook an egg without its shell in boiling water is the easier to explain. It can be traced back through the Middle French verb pochier, with the same meaning, to the noun poche, a bag or pouch. The idea seems to have been that the white of the egg was a container for the yolk. That makes the egg sense of poach a close relative of pouch, of the bag sense of poke (as in not buying a pig in one), and pocket, which is etymologically a little poke. By the end of the seventeenth century this sense of poach had been extended to simmering fish, fruit and other foodstuffs in water.

The other poach, to illegally hunt fish or game, began life in English to mean prod, shove, or roughly push together, to push or stir. This probably came from the Old French pocher, to prod, and is a relative of another sense of poke. This sense of prodding is obsolete in mainstream English but survives to some extent in regional English dialects and in Scots. Later, poach developed into unlawfully encroaching on someone else’s preserve, to trespass. It has a third sense of breaking up ground into muddy patches through animals trampling it.

These three senses puzzle the experts, because they don’t seem to derive from a single word. But there are no other obvious candidates. The mud sense is probably connected with hooves prodding the ground. The illegal hunting sense has been said to be from the idea of figuratively pushing into somebody else’s territory, which by the early 1700s had become linked to taking game illegally as an extension of the idea of trespass.

But it’s also argued that the illegal hunting sense might be from thrusting something into a bag (as in poacher’s pocket, etymologically an intriguing phrase), which would make it a development of the other word. This is supported by Randle Cotgrave’s note in his Dictionary of the French and English Tongues of 1611 that it refers to encroaching on another man’s trade or employment, as the English equivalent of a French expression which speaks of pocketing another man’s labour.

Whatever the source, Mr Bergman, you may safely eat your poached egg without fear of the law.

4. Sic!

• Alan Clayton writes in numerical wonderment, “I just searched Google for a walking route around Reims and one hit was ‘Find over 0 of the best walking routes in Reims ...’. Unfortunately there were only just over -1 of them.”

• The Herald Sun of Australia surprised Barbara McGilvray with news of the supernatural powers of a revered AFL footballer: ‘Robbie Flower will be remembered as one of the finest players to ever pull on the boots after passing away’.

• On 1 October the Weekly Press of Philadelphia had a restaurant review in which Beverly Collins found this: “Nearby, twelve Penn students ate and toasted each other.”

• Bill Clarke found this in the printed instructions from a doctor: “put one drop in the eye four times per day while awake.”