Newsletter 925

02 Jul 2016

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Change in format. Following my move from Pegasus Mail to the Thunderbird email client earlier this year, a few readers have reported problems viewing the HTML version of this newsletter. I have traced these to errors introduced when pasting the text from Microsoft Word into Thunderbird. This issue has been sent using a different method, which I hope resolves the problems.

By hook or by crook. Following the piece last time on this idiom, several readers updated me on the geography of the tale about the invasion of Ireland through Waterford. They pointed out that a village called Crook does exist, on the west bank of the estuary of the River Barrow, while Hook is on the east side.

Hilary Maidstone, among others, suggested that hook and crook aren’t so closely connected in meaning as I had implied. “One thing I thought of as is that a hook in East Anglia — and possibly elsewhere for all I know — is a sharp tool, either for grass (a curved blade similar to a sickle on a short handle) or for hedging (a billhook or billock in Norfolk dialect), a hooked blade on a short handle.” A tool very similar in shape to the modern billhook appears several times in medieval illustrations of pruning grapevines and fruit trees.

2. Yarely/ˈjɛːli/

Alfred Tennyson, poet laureate during much of Queen Victoria’s reign, preferred words of native English origin over those from French and Latin. He’s credited with bringing many old words back into the language. However, his son Hallam wrote a memoir in which he recalled his father regretting that he had never employed yarely.

If he had, his readers would have been as baffled by it as they were with some of his other reintroductions, because by the nineteenth century yarely had fallen out of the standard language, though surviving in some dialects. A rare notable earlier usage that century was in a work by another resurrector of antique words:

“Yarely! yarely! pull away, my hearts,” said the latter, and the boat bearing the unlucky young man soon carried him on board the frigate.

Waverley, by Sir Walter Scott, 1814.

From this, we may guess, correctly, that it means briskly, promptly or quickly. Its source is the Old English gearolíce, related to gearu, ready or prepared.

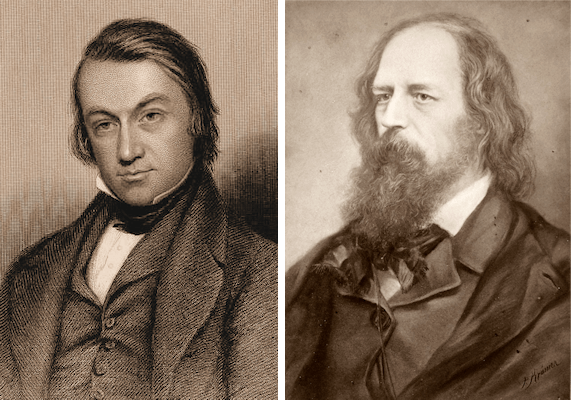

Two lovers of yarely: Charles Mackay and Alfred Tennyson.

The Scottish poet, journalist, author, anthologist and songwriter Charles Mackay (best known for his three-volume work of 1841, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, and the Madness of Crowds) included yarely in his Lost Beauties of the English Language, quoting examples from three Shakespeare plays, including this one:

Speak to the mariners: fall to’t, yarely, or we run

ourselves aground: bestir, bestir.

The Tempest, by William Shakespeare, 1611.

Despite the nautical nature of these two examples, it wasn’t specifically a sailors’ word. However, the Old English gearu became yare, which is still in the seafaring language of North America, meaning a ship that is quick to the helm and is easily handled or manoeuvred.

3. Upset the apple cart

Q From John Hathaway: I know that somebody who says the apple cart has been upset means that somebody’s plans have been ruined, but why an apple cart rather than anything else?

A A figurative sense of apple cart has been around since the eighteenth century. For an unknown but probably trivial reason it’s actually slightly older than the literal use of the phrase.

In the earlier part of its life, the most common sense of apple cart in Britain was the human body. Francis Grose recorded down with his apple-cart in his Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue as meaning to knock a man down; that was in 1788, although the same idea is on record from about 1750. It later became known in Australia:

He slapped her face, she seized a broomstick, and he capsized her “apple cart,” and broke two pannels [sic] of the door.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 16 Apr. 1833.

The etymologist Walter Skeat wrote in 1879, “I think the expression is purely jocular, as in the case of ‘bread-basket,’ similarly used to express the body.”

The form you’re referring to also appears early on. There’s an isolated example on record from Massachusetts in 1788 but it only starts to appear on both sides of the Atlantic in any significant way in the late 1830s:

They won’t encourage trade, or commerce, or manufacturing — because they know that trade, and commerce, and manufacturing would create a power right off that would upset their apple-cart.

Logansport Canal Telegraph (Indiana), 23 Sep. 1837.

The Whigs, Gentlemen, cannot object to the soundness of our old authorities in law, because, you know, they themselves are very fond of referring to the same source, when it suits their purposes; and to deny those authorities, therefore, would be at once to upset their own apple cart.

The Champion and Weekly Herald (London), 16 Apr. 1837.

A cartload of apples, definitely not upset.

We may assume it was around in the spoken language in Britain, lurking out of sight, for longer than the written record shows. It continued in parallel with the human-body sense for most of the 1800s but took until the early twentieth century to become widely popular and to shift from slang to colloquial usage. An early stimulus may have been the widely reported comment by Cecil Rhodes, then prime minister of the Cape colony, that the Jameson Raid of 1895 had “upset the apple cart”. The evidence suggests a peak in the 1930s, possibly helped along by George Bernard Shaw’s play The Apple Cart, first produced in 1929.

The shift in sense from a slang term for the body to ruining a person’s plans seems to have been via an intermediate sense of suffering a personal accident, either involving some external object or simply falling over:

The bed groaned for a moment under the load, and the next moment the strings snapt like tow, and down came the bed, bedding, Dutchman and all, plump into the middle of the cabin floor. ... “You've upset your apple-cart now,” says I as soon as I’de [sic] done laughing.

Huron Reflector (Ohio), 3 Apr. 1832.

If a child falls down you first inquire if he is much hurt. If he is merely a little frightened you say, “Well, never mind, then; you’ve only upset your apple-cart and spilt all the gooseberries.” The child perhaps laughs at the very venerable joke, and all is well again.

Notes and Queries, 13 Dec. 1879.

We’re quite unable to say why some unknown person 250 years ago selected an apple cart as a metaphor for the body because there’s no written evidence on which we can base any reasoned explanation. But we can understand why the idea remains popular in the sense of ruining some undertaking: the visual image of a cart laden with apples overturning — with all its implications for mess, inconvenience and financial loss — is too striking to lose.

It might be worth ending by mentioning an arcane suggestion for the origin of one sense. About 200 BCE, the comic playwright Plautus wrote a line in his play Epidicus that implied Romans had a proverb, perii, plaustrum perculi, which may be loosely translated as “I’m done for! I’ve upset my wagon!” Could this have been the stimulus for the English idiom, with some jesting Latin scholar turning the Roman wagon into a very English apple cart? It’s a nice story, but I suspect that native English wit was capable of creating the image without resorting to second-hand humour.

4. Snooter

Q From Ali Nobari: Wodehouse uses the word snooter, presumably schoolboy slang, but what does it mean?

A It’s possible to get an impression of the meaning of this very unusual word from the contexts in which P G Wodehouse uses it. A couple of examples:

Contains much snootering.

Those who know Bertram Wooster best are aware that in his journey through life he is impeded and generally snootered by about as scaly a platoon of aunts as was ever assembled.

Very Good, Jeeves!, by P G Wodehouse, 1930.

Snootered to bursting point by Pop Bassetts and Madeline Bassetts and Stiffy Byngs and what not, and hounded like the dickens by a remorseless Fate, I found solace in the thought that I could still slip it across Roderick Spode.

The Code of the Woosters, by P G Wodehouse, 1938.

To be snootered is to be harassed, vexed or tormented.

We might indeed reasonably assume that the word is slang from Wodehouse’s schooldays at Dulwich College in south London. But we would be wrong. We would be equally wrong to connect it with the similar snooker, whether the game or the derived verb meaning to put somebody in an impossible position or to trap or entice them. Wodehouse actually borrowed snooter from US slang during his early years in that country.

Snoot as a noun has been recorded there since the 1860s. It’s a local pronunciation variation of standard English snout, a word of Germanic origin that has been in the language since about 1200. The American version was looked down on:

Snoot, of the human face or nose, apparently the same word as snout. A vulgar word in New England. ‘I’ll bu’st your snoot’; ‘hit him on the snoot’. As a verb in ‘to snoot round’, i.e. to nose around, it is reported from Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

Dialect Notes, 1890.

The verb evolved to mean treating a person scornfully or with disdain, leading to the adjective snooty — snobbish, supercilious or stuck-up, figuratively with one’s nose in the air in a superior way.

Wodehouse created snooter from snoot, presumably developing it from the sense of snubbing someone; he used it often enough — in at least eight of his books as well as in correspondence — that he became identified with it, so much so that the Oxford English Dictionary’s entry for the word has examples only from him. A couple of writers have since employed it, but it’s very rare.

5. Fard

I was consulting an old book when the Empress Poppaea’s name came up. You surely remember her: second wife of the Emperor Nero in ancient Rome, notorious for her intrigues, and commemorated in the clerihew:

The Empress Poppaea

Was really rather a dear;

Only no one could stop her

From being improper.

The context was her skincare routine, which was like nothing seen in Rome before. It wasn’t just the daily baths in asses’ milk, but also the then newfangled overnight face packs of damp barley meal, followed by the daytime application of chalk and white lead.

The book introduced me to fard, to paint the face, and to the noun fard, a cosmetic.

Another example:

I think, that your sex make use of fard and vermillion for very different purposes; namely, to help a bad or faded complexion, to heighten the graces, or conceal the defects of nature, as well as the ravages of time.

Travels Through France and Italy, by Tobias Smollett, 1766.

Definitely a fard user: the Empress Poppaea.

English borrowed fard from French in the sixteenth century but abandoned it again in the nineteenth. Though fard would be a usefully brief alternative to “put on one’s makeup”, the chances of hearing comments like “I farded in the train on the way to work” are rather small.

If you know French, you may have guessed what this word means, since it’s still in that language in the sense of cosmetics or makeup (and it does have a verb meaning to put on makeup: farder). Nobody knows for sure where the French word came from: one suggestion is the Old High German farwjan, to colour, ancestor of the modern German verb färben. In its early years in French fard could figuratively suggest a misleading appearance or language, which survives in the idioms parler sans fard, to speak candidly or openly, and vérité sans fard, the plain or unvarnished truth.

Fard in English often specifically meant a white face paint (hence Smollett’s “fard and vermillion”, contrasting white and red). It was either the ancient unguent of lard mixed with white lead or a similar concoction based on a brilliant white compound of bismuth, sometimes called blanc de fard. Both were poisonous and long-term use damaged the skin.

The word occasionally appears as a deliberate archaism:

A trio of women holding hands, gaunt and thin as the inmates of a spitalhouse and attired the three alike in the same cheap finery, their faces daubed in fard and pale as death.

Cities of The Plain, by Cormac McCarthy, 1998. A spitalhouse, where spital is a shortening of hospital, is a place set aside for the diseased or destitute, usually of a lower class than a hospital.

6. Sic!

• A mysterious headline from the Western Mail of 4 June the following headline left Kate Lloyd Jones’s son puzzled about the size of the capsules mentioned: “Parents in laundry capsules ‘mistaken for sweets’ alert.”

• A widely reproduced item from the news agency AP, which Brian McMahon saw on 4 June, implied remarkable medical self-help at a car rally accident: “One spectator at the event ... broke an arm, while a woman received multiple injuries and a third person was forced to amputate a leg.”

• A geologically improbable opening to a report of 8 June in the Hamilton Spectator of Ontario, Canada, understandably intrigued Ari Blenkhorn: “It had been a long drive. ... By 2:50 a.m. Monday morning, though they couldn’t see them in the darkness, the rolling hills of Alabama gently rocked the car.”

• Ian Harrison received a spam email from a South African cheap-deals site on 15 June, promoting a manual meat grinder which it claimed, “Can Be Used To Grind An Assortment Of Meats And Ingredients Made Of Cast Iron.”

• A headline on 9 June in the Dominion-Post of Wellington, New Zealand, attracted Michel Norrish’s attention: “Grapes grown in graveyard produce a full-bodied wine”.

• On 14 June, Alec Cawley found that the BBC news website had this about a banned Malaysian Airline: “It has two Boeing 737-400 planes in its fleet, each able to carry about 180 passengers, eight pilots and 50 crew.” Overstaffed, perhaps?