Newsletter 864

11 Jan 2014

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Squared away “During basic training in the Royal Fusiliers,” Peter Taylor recalls, “we had to open our lockers for regular inspection. Shirts, underwear and socks had to be not only immaculately folded, but reinforced with cardboard so everything appeared rectangular. As this was nearly 60 years ago, during National Service, I can’t be certain whether the phrase was squared away or squared up. The whole experience was so mind-numbing that I would rather not think about it too much!”

Sir Peter Bottomley wrote that squared away reminded him of all Sir Garnet, the one-time army equivalent of Bristol fashion. The latter is a short form of all shipshape and Bristol fashion, known from the 1820s in reference to the excellent condition maintained by ships based in Bristol, then one of the richest and most important ports of England. The former derives from Sir Garnet Wolseley, a famous soldier who led many successful military campaigns in the 1870s in Canada, the Gold Coast, southern Africa and the Sudan. He was hailed as the master of the small war, did much to reform the army and was caricatured by W S Gilbert in The Pirates of Penzance as the very model of a modern major-general. His soldiers used the expression so much that it became transformed into all Sigarneo or all Sigarno, all is in order or everything’s OK.

Conformator Colin Houlden commented on one of the other technical terms in last week’s piece. “My father used to be a hatter and I seem to recall — this is over 70 years ago! — that there were two types of tolliker. The foot tolliker formed the brim at right angles to the foot of the crown or upright part of the hat, while the tolliker produced the indentation on the top of the crown. The foot tollikers were of wood and made to fit either the right or left hand and looked rather like an iron (for clothes) on the end of a curved handle. The tollikers to produce the ‘crease’ in the crown were also of wood and looked like an iron with no handle with a pear-shaped indentation in its top.”

2. Dulcarnon

Geoffrey Chaucer included this in his poem Troilus and Criseyde of about 1374. Criseyde says that she’s in a dulcarnon over something and is at her wits’ end. This led to I am at dulcarnon meaning that the speaker is utterly perplexed or at a complete loss.

In the middle of the nineteenth century increased interest in the works of Chaucer and the history of language led to scholars being deeply puzzled about dulcarnon. No other word like it existed in English and its own origins were unknown.

The matter was eventually cleared up by the famous philologist and Chaucer scholar Professor Walter Skeat. He worked out that it’s from Arabic dhu’lqarnayn, two-horned, an epithet applied to Alexander the Great because he claimed descent from Amun, a god of ancient Egypt who was often depicted with ram’s horns.

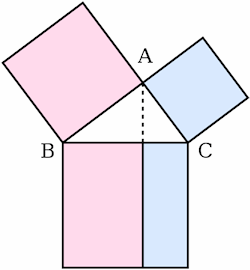

When Euclid wrote his famous Elements of Geometry, he illustrated Pythagoras’s theorem by a diagram showing squares built on the three sides of a right-angled triangle. The way the picture was oriented made the upper two look fancifully like horns and in medieval times they were known to irreverent or exasperated students as dulcarnons. Many found Pythagoras’s theorem impossible to understand and dulcarnon came to mean an irresolvable puzzle.

Chaucer had Criseyde’s uncle Pandarus tell her that a dulcarnon was also called the flight of wretches. Unfortunately, he had his Euclid confused. This actually referred to a different proposition, known in Latin as the fuga miserorum or the pons asinorum, the bridge of asses. It proved that the angles opposite the equal sides of an isosceles triangle are themselves equal. This was the first real test of intelligence for someone studying geometry and anyone who couldn’t understand it was unlikely to be able to master the rest of Euclid.

Dulcarnon has been confused with horns of a dilemma. However, that refers to being forced to choose between two equally unsatisfactory alternatives, not being at a loss how to proceed at all.

3. Wordface

Quaking cold The extreme cold in Canada earlier this week led to the appearance of the term frost quake. In Toronto, for example, there were reports of hundreds of people being startled by loud booms that resembled gun shots. The cause was water deep in the ground becoming frozen and expanding, causing explosive cracking of the soil. The scientific term for it is cryoseism, described in a work of 1980 as “a non-tectonic earthquake caused by freezing action in ice, ice-soil and ice-rock materials”. Though rare outside the polar regions, they’re known in Canada and the northern states of the US and the term frost quake is much older than some reports have suggested. In January 1918, for example, two newspapers in the Boston area reported, in small news items on an inside page, that people were woken and houses shaken as the result of a frost quake, so named. The Boston Globe noted in a subheading “Frost quakes not uncommon in Maine, but rare in Bay State.”

Guff gets prizes Lucy Kellaway announced her 2013 Golden Flannel awards for corporate linguistic foolishness in the Irish Times last Monday. The prize for the best euphemism for firing people went to HSBC for demising; she commented that “it has done the impossible and invented a euphemism that is harsher than the real thing.” (There’s a word for that: dysphemism.) Last month, Michael Bellas of Nestlé described a bottle of water as an “affordable, portable lifestyle beverage” and so got the award for the best rebranded common object. There’s more in the article.

Because because The choice of because X as the Word of the Year by the American Dialect Society has led to much confused comment. As an example of the grammatical difficulties accompanying this word, as much in its conventional usages as the new one, see Professor Geoffrey Pullum’s mind-stretching discussion on Language Log. He says that dictionaries wrongly call because a conjunction “because they are all lazy followers of a stupid tradition that has needed rethinking for 200 years.” He argues that the word is a preposition. You may find it hard work following him, but the destination is worth the journey. If you would like a different view, pop over to Gretchen McCulloch’s blog All Things Linguistic, in which she argues the opposite view, that because in the new construction isn’t a preposition.

4. Sizzle and steak

Q From Pierre Leteurtre, France: I heard someone say in the BBC World Dateline London programme, “He is all steak and sizzle”. Does this mean “in totality”? Somewhat like lock, stock and barrel and so many other figurative sayings?

A You’re right to be puzzled by this. Assuming you didn’t mishear, it’s likely the speaker (who would have been a foreign correspondent based in London) misspoke the idiom. The idiom is properly he’s all sizzle and no steak, meaning that the person being spoken about had an appearance of ability but was actually ineffective.

He might have borrowed another idiom with the same sense and said the person was all talk and no action or — in the Texan version — all hat and no cattle. The idea behind all sizzle and no steak is that you figuratively get the anticipatory sound of the frying, perhaps even a delicious smell, but that in the end nothing appears except disappointment. A modern example:

House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) responded Thursday by describing Obama’s initial speech as having “all sizzle and no steak.” He added: “That’s assuming that there is any sizzle left after you’ve reheated this thing so many times.”

Washington Post, 26 Jul. 2013.

The idiom is American but the first example that I’ve found in the historical record in the current form is actually from a debate in the Irish parliament, the Dáil, in 1962:

I think the Minister will concede that this Bill is all sizzle and no steak.

For its origin we have to go back at several decades further, to the man who has been called the greatest salesman in the world. He was Elmer Wheeler, who codified years of selling during the Depression in a 1937 book on salesmanship called Tested Sentences that Sell. Among them was a line that’s been called the most famous piece of sales advice ever given and which gave him the nickname “Sizzle”: “Sell the sizzle not the steak” (he also wrote it as “Don’t sell the steak — sell the sizzle”). His argument was that a good salesman tells a potential customer what the product will do for him, not what it is. He wrote:

Sell the bubbles, not the champagne. Sell the pucker, not the pickles. Sell the whiff, not the coffee. Sell the extra freshness, not the eggs. Sell the flavor, not the butter.

Of course, after all the salesmanship is done and the sizzle has sold the steak, something tasty and filling has to be presented to the buyer; sell the sizzle without the steak and you’re a fraud. Somebody who’s trying hard to impress with his abilities had better come up with some steak to match his sizzling sell. Hence the disparaging quip, all sizzle and no steak.

5. Sic!

• “Dangling modifier of the day,” Martyn Cornell emailed on Tuesday, having seen this in the Derby Telegraph: “Despite being diagnosed with breast cancer in 2008 and undergoing months of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the pub grew in popularity under Mrs Muldoon.”

• Bruce Greyson encountered this in the Charlottesville Daily Progress on 4 January: “One proposed rule change aims to clarify terminology used by federal laws to prohibit people from purchasing a firearm for mental health reasons.” He commented, “As a psychiatrist, I am hard-pressed to think of a good mental health reason to purchase a firearm.”

• Alan Clayton found that an edition of the translation by Constance Garnett of a classic Russian novel was being advertised on Amazon as The Brother’s Karamazov. A hiss and a boo to the publishers, E-artnow. Its cover not only has the apostrophe but it’s the wrong way round.

• Don Donovan wrote: “Sky TV News in New Zealand reported on 6 January that to aid victims of the polar vortex, US authorities had set up a ‘Hypothermia Hotline’.”

• On this side of the Atlantic, an electricity pylon is a transmission tower. Eoin C Bairéad’s message had the subject “Irish engineering wonders” and referred to a report on the website of Clare Community Radio of 7 January: “The Government says it is not realistic or financially feasible to run new electricity pylons underground.”

6. Useful information

World Wide Words is copyright © Michael Quinion 2013. All rights reserved. You may reproduce this newsletter in whole or part in free newsletters, newsgroups or mailing lists online provided that you include the copyright notice above. You need the prior permission of the author to reproduce any part of it on Web sites or in printed publications. You don’t need permission to link to it.

Comments on anything in this newsletter are more than welcome. To send them in, please visit the feedback page on our Web site.

If you have enjoyed this newsletter and would like to help defray its costs and those of the linked Web site, please visit our support page.