Alas Poor Nell

Some personal names have undoubtedly gone down in the world.

At one time Wally was just a common Northern abbreviation for Walter, but it has relatively recently became transmogrified in Britain into a mild term of abuse for a person who is “foolish, inept, or ineffectual”, to quote the OED. It is also a name given to a type of pickled gherkin in some parts of the country, a use I note which has not yet made either the OED or the new edition of the Concise Oxford.

The heir to the British throne has another unfortunate name: in Britain someone called Charles is often familiarly called Charlie, but a Charlie, in full a proper Charlie or a right Charlie, is also a person lacking in common sense, a fool. In this meaning it was originally US slang, I believe, taken up and rapidly naturalised in Britain only after World War Two. It took hold so quickly perhaps because the word has long been used in British slang in other senses, such as a nightwatchman and in the plural as a term for the female breasts. The former came about because — so it is said — the night watch was reorganised by Prince Charles’s eponymous predecessor, Charles I, though the term isn’t recorded until 150 years after Charles I lost his head.

Even more unfortunately, the next in line for the crown after Charles is his son William, and willie is a rather childish British name for the penis. A more adult word for it is the ancient diminutive for Richard, dick. Come to that, so once was Johnnie, which was also once a term for the condom. (While we’re in this area of life, an American friend was very surprised at the response when he announced his name at a party during a visit to London: “Hi, I’m Randy”. He hadn’t realised that randy in Britain is not a name but a common slang term meaning “lustful, sexually aroused”. Not a name that travels well.)

Nell Gwyn

But the name that I feel has had the worst deal is Nell or Nellie, originally just an affectionate abbreviation for Eleanor or Helen. I blame the other royal Charlie for this, King Charles II. Somehow the pathos of his supposed dying words to his brother James, “Let not poor Nelly starve”, has stuck to the name ever since. Why else would Charles Dickens choose it for the name of his doomed and pathetic heroine in The Old Curiosity Shop? Oscar Wilde was right: “I defy any man to read of the death of Little Nell without laughing”. And it’s hardly possible to imagine Escoffier creating Peach Nellie.

Charles’s deathbed words may have contributed to the establishment of Nell or Nellie in a range of set expressions. The name came to be used particularly of someone of low birth and limited capabilities. For example, Nellie was a fairly common generic name for a lowly servant, a skivvy (a word, by the way, which is one of the very limited number in English containing two v’s next to each other; searching them out would certainly make a better competition than finding three words ending in “gry”). Someone new in a factory or office would often have been instructed through sitting by Nellie, or in other words learning by watching some conscientious and not too clever person who knew the ropes but who could be relied upon not to inculcate bad habits. The word also became a slang term for an effeminate male or homosexual, and in the US gave rise to the derogatory nervous Nellie for an excessively timid person. In the same country, we have since heard nice-nellyism, “prudery; genteelism; excessive prudishness of speech or behaviour”, which gives us a clue to Mrs Grundy’s given name.

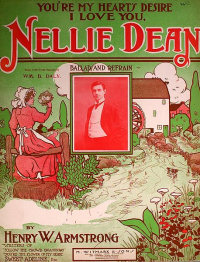

There was a famous old music-hall song, whose chorus I can remember my father singing (he was born a Victorian, so probably heard it in a real music hall shortly after it first appeared):

There’s an old mill by the stream, Nellie Dean,

Where we used to sit and dream, Nellie Dean.

And the waters as they flow

Seem to murmur sweet and low

You’re my heart’s desire; I love you, Nellie Dean.

Nellie Dean, lyric by Henry W Armstrong, 1905.

For a while it became the archetypal pub drinking song: imagine it lugubriously belted out with a skinful of beer lubricating every voice. There was a real Nellie Dean on the boards shortly before, a minor music-hall performer described on the bills as a serio-comic. Surely this song wasn't hymning her?

Another curious expression that my father used back in the 1940s was not on your Nellie, which some authorities think had been imported from the USA about ten years beforehand. Like Charlie it sounds home-grown, to the extent that it has been suggested that it is actually a piece of London-based rhyming slang: Nellie = Nellie Duff = puff. There was certainly an older slang phrase in existence: not on your puff, meaning “not on your life; never” in which puff means “breath” and so “breath of life”, life itself. To suggest that it was rhyming slang needs some explanation of this supposed person Nellie Duff. Duff has a number of senses. One of them is in plum duff, where it’s a regional pronunciation of dough. Another sense is “useless; rubbish; counterfeit”, once a common British word, and one which was taken to the US by Scottish settlers. So it is probable that the two mildly disparaging words were put together just to make the rhyme.

Nellie Bly.

There’s yet another Nellie expression, Nellie Bligh, that at various times has meant a lie, a fly, or (particularly in Australia), a pie. The source of this version remains in dispute. It has been argued that it comes from the name of the “other woman”, Nellie Bly, in the sentimental ballad Frankie and Johnny; I've hankered after a connection with Captain Bligh of the Bounty. The most probable origin is the famous pioneering nineteenth century American woman journalist Elizabeth Jane Cochran. She took the pen name Nellie Bly from the title of a currently popular song by Stephen Foster. As the slang term Nellie Bligh is regularly so spelled, its recorders may have been influenced by that other Bligh.

Now Nellie Duff isn't a totally unknown name in real life (there was a ship of that name once). I’d love to find that there was a real Nellie Duff who gave her name to the expression and that there might be an opportunity to ask her shade (for she surely must by now have passed to her heavenly reward) what she thought of it. If it were me, I’d have changed it, quick.