Katy bar the door

Q From Bob Welborn: I have been looking for the origin of Katy bar the door. Any ideas?

A Various sources down the years have suggested at least three. However, the more one investigates, the further away a simple answer seems to get.

The idiomatic expression Katy bar the door! (also as Katy bar the gate! and with Katie instead of Katy) is an American exclamation of the later nineteenth century, at one time most common in the South. The speaker is warning that trouble lies ahead. It’s still common:

[W]hen we abandon the belief in absolutes — such as telling the truth, being honest, and doing what is right — then Katy bar the door because there is no compass to guide us and our actions.

Galveston County Daily News (Galveston, Texas), 9 Nov. 2013.

William and Mary Morris’s book The Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins suggests that it derives from a traditional ballad, most probably the medieval Scots one usually entitled Get Up and Bar the Door, still widely known and sung. But no version I’ve found mentions Katy anywhere. The ballad tells the tale of an argument between man and wife about who should bar the door. They agree that the first who speaks will do so. Neither speaks, and neither bars the door. At night, robbers enter through the open door. Though the ballad is really a wry commentary on marital obstinacy and its consequences, the lesson is that not barring the door has led them to trouble. It’s conceivable that “bar the door!” was adapted from it to suggest unpleasantness lies ahead.

In 1941, the renowned American language researcher Peter Tamony issued an appeal for information about the expression. In response, the even more renowned Damon Runyon wrote a little tongue-in-cheek squib, syndicated in newspapers on 9 March that year, which told how a fine Irish lass called Katherine Sullivan Jale came over to America before the Revolution. She and her husband worked a trick on Native Americans by which she would entice them into her log cabin so her husband could scalp them and sell the hair. As soon as one was inside, her husband would holler, “Katie, bar the door” and get to work. This product of a mischievous imagination may be why some people have suggested the idiom was originally Irish. Please don’t perpetuate it, or the waters will be still further muddled.

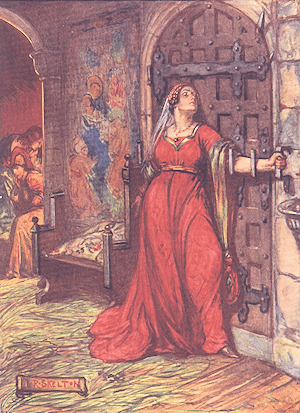

Catherine Barlass, by J R Skelton, from H E Marshall’s Scotland’s Story of 1906.

Many World Wide Words subscribers pointed to a quite different story that involved one Catherine Douglas. Under attack while staying at the Dominican chapter house in Perth on 20 February 1437, King James I was holed up in a room whose door had the usual metal staples for a wooden bar, but whose bar had been taken away. The legend is that Catherine Douglas, one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting, tried heroically to save the king by barring the door with her naked arm. Her attempt failed and the King was murdered, but she was thereafter known as Catherine Barlass. Dante Gabriel Rossetti wrote a poem about her in 1881, entitled The King’s Tragedy, which has been suggested as the direct source of the saying, but the nearest Rossetti comes to the usual form of the expression in the poem is “Catherine, keep the door!”

In any case, we now know that it can’t be the source because US researcher Bonnie Taylor-Blake has found examples that predate publication of Rossetti’s poem. This one, from two years before, shows that the idiom was already fully formed in the same sense as today:

To sum it all up, my advice to anyone thinking of going there would be “don’t,” unless they have a pocketfull of the “rhino” which they can afford to lose. I saw it was “Katy bar the door” with me unless I skipped, and I lost no time in skipping.

The Democrat (Lima, Ohio), 30 Oct. 1879.

A rather earlier one hints at a possible source:

The Custom House Packet, with the Custom House colored band, U.S. Marshal Packard, in command, with the old flag triumphantly kissing the breeze of old Red, the band playing “Katie, Bar The Door,” and with waving rags touched the wharf and proceeded to land her precious cargo.

The Louisiana Democrat (Alexandria, Louisiana), 2 Oct. 1872.

So the implication once again is that a popular melody may be involved. We have no way of knowing if the tune’s title was the source or if its authors were referring to something older that’s now lost to us. The context was an African-American event, the Radical Custom House Colored Jubilee, on the banks of the Red River at Alexandria, which may suggest a link with black popular music. But nobody has yet been able to establish what the band was playing and its title doesn’t appear in the various comprehensive online archives of American popular music. Jonathon Green suggests in his Green’s Dictionary of Slang that it was a popular American fiddle tune, though he gives no further information, nor any indication of how or why its title should be connected to the idiom.

Sometimes, this etymology lark can be just too frustrating for words.