In the Land of Invented Languages

“Ĉu vi parolas Esperanton?” If you’re able to say “jes” in reply, you’re a member of a smallish group who knows that it means “do you speak Esperanto?”, the language that was created by Dr Ludwig Zamenhof in Poland in the 1880s. I learned a little as a teenager, to the extent that — to my own mild surprise — I could still today write that sentence without having to look it up.

Arika Okrent’s experience began with the very different Klingon. It was invented so that the aliens in Star Trek could speak in a macho warrior tongue that sounded sufficiently unEarthly. If you know that “tlhIngan Hol Dajatlh’a’?” means “do you speak Klingon?”, you are also a member of a minority group, one irretrievably and rather sadly tarred with the brush of ultra-geekdom. I must confess to at least semi-geekdom, since I have a copy of The Klingon Dictionary on my shelf, written by Marc Okrand; he built on a few words invented by James Doohan (Scotty) for Star Trek: The Motion Picture to make a detailed language for Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.

Klingon and Esperanto are, of course, utterly different in form and purpose, the one created as a way merely to make an entertainment more linguistically plausible (albeit one that has achieved a life beyond Star Trek), the other designed with the deeply serious — if naive — intent to promote world peace by helping people to talk to each other (English has become widely used internationally in the century since Zamenhof, but conflict hasn’t noticeably reduced). They are perhaps today the two most widely known examples from an astonishingly large collection of invented languages. More than 500 of them are listed in an appendix. Europal, Simplo, Geoglot, Volapük, Ulla, Novial, Ehmay Ghee Chah, Basic English, Tutonish — the vast majority are now just footnotes in obscure scholarly texts.

Early created tongues arose out of the scientific rationalism of the seventeenth century. Natural languages were criticised, fairly enough in one way, for their design flaws: they’re irregular, full of idioms that make no sense to a learner and contain words with more than one meaning while sometimes lacking words for concepts we need. How much better it would be, philosophers felt, if one could be designed from scratch on logical principles. Many have tried, as Arika Okrent explains. Her main example is that of John Wilkins, a member of the Royal Society, who published his detailed attempt, A Philosophical Language, in 1668. All such languages were rooted in attempts to classify the whole of human knowledge, which their inventors only gradually came to realise was an impossible endeavour. A similar idea, but based on modern mathematical logic, surfaced in the 1960s as Loglan (and its successor Lojban), a language designed to test the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, that the structure of a natural language influences the way its speakers think about the world.

Another type appeared as a result of a more pragmatic attitude in the nineteenth century. This focused on creating languages that were easy to learn and would help people to communicate. Esperanto is the classic example but there are dozens of others. A third class of invention grew up in the twentieth century – languages based on pictorial symbols, such as Blisssymbolics or aUI, which sought to avoid what their authors saw as the tyranny of words. Yet a fourth kind was the result of a personal artistic and linguistic impulse — to create a tongue that was satisfyingly complex and complete. The most famous examples here are J R R Tolkien’s elven tongues Quenya and Sindarin in his Lord of the Rings trilogy. Interest in making artificial languages is currently high through Internet discussion groups that specialise in conlangs (constructed languages) and artlangs (artistic languages invented to give aesthetic pleasure).

Arika Okrent wittily tells the stories of many of these invented languages, as well as of one natural language — Hebrew — that in effect was recreated in the twentieth century some two millennia after it vanished as a native spoken language. She focuses as much on the men who created the languages and the cultures in which their creations were born (and almost invariably soon died) as on the languages themselves, though she discusses a number in enough detail for readers to get a good feel for them. Her personal and entertaining book wears her research lightly. It will be a good read for anyone with even a general interest in this aspect of linguistics.

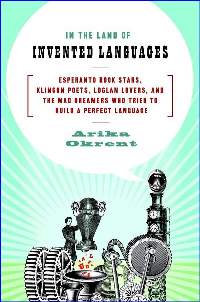

[Arika Okrent, In the Land of Invented Languages; published under the Spiegel & Grau imprint by Random House, New York, May 2009; hardback, 341pp, including index; publisher’s list price $26.00; ISBN13: 978-0-385-52788-0; ISBN10: 0385527888.]